By LEONIDAS DONSKIS.

Lithuania cherishes her historical memories of once having been a multi-ethnic, multi-religious and multi-cultural country. It also cherishes the most generous and noble-spirited traditions of the Romantic ethos of liberal nationalism, and quite justifiably so. In the late 1980s, Lithuania’s national movement of rebirth, Sajūdis, and its “singing revolution” not only revived the spirit of the nineteenth century epoch of the springtime of the peoples (whose slogan – “For your and our freedom!” – was raised as the banner), but also became a litmus test of the Soviet policy of glasnost and perestroika. As the first breakaway republic in the former Soviet Union, Lithuania came to embody the historic triumph of East-Central Europe’s time-honored strug gle for freedom.

It was with good reason that the great Polish Romantic poet Adam Mickiewicz, who was born in Lithuania and who regarded Lithuania as his motherland, depicted Lithuania as a mysterious country, which, repeatedly, disappears from history and then returns to it. In 1918, Lithuania declared her independence after one hundred and twenty-three years as a part of Czarist Russia. In 1990, Lithuania restored her independence after fifty years of political and cultural isolation from the rest of the world. And in each time, Lithuania came back into existence through the revival of her historical memory and culture, rather than through the exercise of power. Culture is what led Lithuania from a political non-entity to that of a political presence. Her culture paved the way for politics, and not the other way around.

Lithuania had long had at least two visions of how to fulfill herself as a modern historical actor. One of them, as mentioned, deals with Lithuania as a multi-ethnic, multi-religious and multi-cultural country deeply grounded in the political and cultural realities of the Renaissance and Baroque eras. The other underlines Lithuania as having her roots in Romanticism – the Lithuania of mystical influences, spirituality and organic community. Both visions and interpretations of Lithuanian culture could be are richly supported by historical evidence.

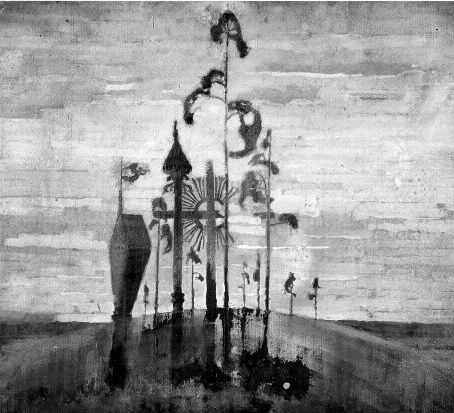

The vision of Renaissance and Baroque Lithuania is inseparable from the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, a unique political entity that preceded the EU centuries earlier and in more than one way. That of neo-Romantic Lithuania is deeply permeated with archaic and pagan layers of culture and Roman Catholicism – a blend of archaic religious artwork and a modern, more or less neo-Romantic, mythology of history and culture. It represents a combination of wooden sculpture and architecture, profoundly archaic in its form and character, and modern mysticism, the latter best represented by the composer and painter Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis.

A CULTURAL BRIDGE

In the first half of the twentieth century, Lithuania’s self-image came into existence in the form of a moderate messianic construct, casting this small nation as an important bridge between East and West, the former often reduced to Slavic civilization or Russia. The concept of a synthesis of civilizations – East and West – was elaborated by the L i t h u a n i a n philosopher Stasys Šalkauskis, particularly in Sur les confins de deux mondes [On the Boundary of Two Worlds, 1919], a book on Lithuania he wrote in French at the University of Fribourg in Switzerland. History claimed that the Republic of Lithuania became an actor on the inter-war European political stage for only a short period of time, from 1918 to 1940 until it was occupied and annexed by the Soviet Union. This concept of Lithuania’s being on the boundary of two worlds and bridging the civilizations of East and West, elaborated in other works of Šalkauskis, was instrumental in an effort to reflect on the new state’s place in the world and also in its cultural and educational policies.

Interestingly enough, Šalkauskis argued that Lithuania should never confine herself to one particular pattern of culture. Instead, he insisted, Lithuania should reconcile and embrace, within the limits of her identity and trajectories of consciousness, Germanic, Romance and Slavic influences. The more cultures and influences Lithuania embraced, her complex history and culture would become more conscious and known.

Much ink has been spilt since then arguing if it makes sense to take this vision seriously – particularly now when Lithuania has become a member of the EU and NATO, qualifying for membership in clubs that were supposed to be beyond reach for such a long time. Yet we should not forget that Šalkauskis’s concept of Lithuania as a bridge between the civilizations of East and West and stress the importance of culture conceived of as a concert of nations and their educational process, instead of political domination or power.

Lithuania’s accession to the European Union, and also joining NATO, was arguably one of the pivotal events in Lithuanian history. It invites reconsideration of what happened to Lithuania over the past twenty four years. There is little doubt that Lithuania has already achieved a turning point in her history, which might be compared only to her baptism in the fourteenth century. A latecomer to Christianity and modernity, a country with several planes of cultural and civilizational identity, Lithuania seems finally to be on her way to integration in the Western system of trade and security.

A MIRACULOUS EMERGENCE

Historically speaking, Lithuania is an old polity, which dates back to the early Middle Ages. It has an ancient language and an old culture both recalled and revived during the national rebirth movement in the nineteenth century. One of the greatest powers in medieval Europe whose territory stretched from the Baltic Sea to the Black Sea, she eventually crumbled and lost her influence in modern Europe. Bearing in mind the fact that the country was part of Tsarist Russia from 1795 to 1918, that the Lithuanian elite adopted the Polish language and finally, that Lithuania underwent considerable Russification in the nineteenth century, the emergence of the Republic of Lithuania in 1918 was nothing short of miraculous. Yet Lithuania enjoyed parliamentary democracy for just eight years: a coup in 1926 replaced the democratic regime with a mildly authoritarian rule until the Soviet invasion of 1940 . Incidentally, this was the case in all three Baltic states.

At the same time, Lithuania would be unthinkable without her magnificent Jewish legacy. Prior to the Second World War, Lithuania was famous for her very large Jewish community. About 240,000 Jews lived in Lithuania; yet only 20,000 survived the Holocaust. The Lithuanian capital, Vilnius was occupied by Poland from 1920 to 1939 and was known around the world as the Jerusalem of the North, the home of many internationally eminent Jews. Needless to say, the history of Jewish civilization would be unthinkable without Lithuania’s Jews – the Litvaks.

Suffice it to recall those Litvaks whose names are inscribed on the cultural map of the twentiethcentury world – the philosophers Emmanuel Lévinas and Aron Gurwitsch, the painters Chaïm Soutine (a close friend of Amedeo Modigliani in Paris), Pinkus Krémčgne, Michel Kikoine, Marc Chagall (all these painters were related to Belarus and, in one way or another, to Lithuania – most importantly, all were Litvaks) and Neemija Arbitblatas, the sculptor Jacques Lipchitz, the violinist Jascha Heifetz and the art critic Bernard Berenson. In sum, Lithuanian cultural history reads like an exciting novel, or even an adventure story. Small wonder that much of it remains to be discovered by our fellow Europeans. The same applies to us – only now does Lithuania appear to be capable of truly challenging herself and offering new interpretations of her complex historical past. ?

Leonidas Donskis, Ph.D., a Member of the European Parliament, attended the 30 year Anniversary of the Endowed Chair of Lithuanian Studies. We print here in part some of his comments which he delivered at the time.

DRAUGAS NEWS Lithuanian World Wide News in English

DRAUGAS NEWS Lithuanian World Wide News in English