By Daiva Markelis.

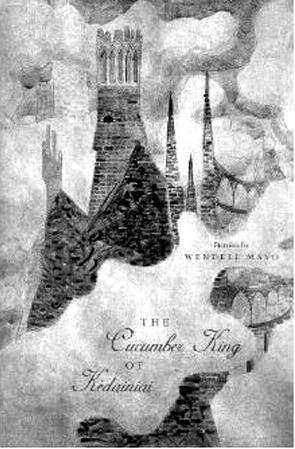

Wendell Mayo, a native of Corpus Christi, texas, is an accomplished american writer. over one hundred of his short stories have appeared in magazines and anthologies, including Yale Review, Harvard Review, Missouri Review, Boulevard, Prism International, and others. he is the author of four short story collections. two of his books of short stories are set in Lithuania. these are In Lithuanian Wood, which was published by White Pine Press in 1998, and The Cucumber King of Kėdainiai, which was published by subito Press in 2013 and was the winner of the subito Press award for innovative Fiction, sponsored by the university of Colorado at Boulder. In Lithuanian Woodwas translated into Lithuanian and published by Mintis Press under the title Vilko Valanda. Wendell Mayo is a recipient of an nea fellowship and a Fulbright to Lithuania. he teaches creative writing at Bowling green state university.

Wendell Mayo has visited Lithuania many times. From 1993 to 2004 he traveled to Lithuania each summer as part of the aPPLe program (the american Professional Partnership for Lithuanian education). aPPLe is a volunteer, international, non-profit educational organization which partners with Lithuanian educators to foster innovations in education. about 300 american and Canadian educators and teachers belong to aPPLe. each summer aPPLe members conduct seminars in Lithuania for Lithuanian teachers. Wendell Mayo has participated in many aPPLe seminars, and after a ten year hiatus returned this summer to teach creative writing in Kaunas. he also provided the keynote address, “Let Me tell You a story: narrative as Pedagogy.”

Recently, daiva Markelis interviewed Wendell Mayo about his award-winning collection of stories The Cucumber King of Kėdainiai. Ms. Markelis is an accomplished writer in her own right. in 2010, the university of Chicago Press published daiva Markelis’s memoir, White Field, Black Sheep: A Lithuanian-American Life. her creative nonfiction has appeared in New Ohio Review, Crab Orchard Review, The American Literary Review, Oyez, The Chicago Tribune Sunday Magazine, Writing on the Edge, Women and Language, The Chicago Reader, Mattoid, and The Fourth River. her short stories have been published in The Cream City Review andOther Voices. she teaches creative writing, composition and rhetoric, and women’s memoir at eastern illinois university.

For many Lithuanians the title of Wendell Mayo’s most recent book, The Cucumber King of Kėdainiai, appears to refer to a notorious politician in Lithuania, Victor uspaskich. uspaskich was born in russia in 1959 and came to Lithuania in 1985. he developed a large business empire in food production, animal fodder and importation of natural gas. he became a Lithuanian citizen and entered politics. in 2003 he formed a political party called Darbo Partija (Workers Party or Labour Party). in 2006 his political party was involved in a financial scandal. in 2013 uspaskich was convicted of tax fraud and sentenced to 4 years in prison, but he has avoided his sentence by claiming immunity from imprisonment as a member of Lithuania’s parliament. Wendell Mayo’s book is a collection of short stories, only one of which centers around uspaskich and his luxurious residence.

Here are a few excerpts of the conversation Daiva Markelis had with Wendell Mayo at the editorial offices of draugas last fall.

WENDELL MAYO AN AMERICAN WHO WRITES SHORT STORIES ABOUT LITHUANIA Wendell: This is the twentieth year that I’ve been writing stories set in Lithuania. I guess the question is – if it’s not on your mind, then it’s always on mine – why do I write about Lithuania? I think it’s because the story of Lithuania is the story of displacement. It’s also a story of a journey home. For me, as a writer, Lithuania’s story is as old as the story of Moses. It’s as old as The Odyssey: the need to find a home, to seek “home.” So why not? In my mind the story of Lithuania is one of the greatest stories of all time. Why wouldn’t I want to write about great subjects, being a writer? So after twenty years of writing about Lithuania, it’s become more than my subject. It’s become a part of me. It’s easy to say that my wife’s influence (who is herself Lithuanian- American) has rubbed off on me. She urged me to go to Lithuania in 1993 with APPLE, but from then on I didn’t need her influence as much. I found Lithuania on my own.

Daiva: I would like you to talk about the Cucumber King, how you wrote this story, and anything else you want to say about this story and this individual

Wendell: I will start with the origin of the story and then I’ll get to Viktor Uspaskich. I first heard the story in 1998 from Vaiva Vebraite in Vilnius. We were at a bar, “Mano Liza”. We were drinking beers and Vaiva said, “Well, I have to tell you the story of the Cucumber King.” She had actually visited his castle with other American teachers. She said, “You’re a writer, and this is so strange that you have to write about it.” For many years the story just simmered in me until I wrote about him. At the time, I knew the Cucumber King was a real person, and a good deal of the story is based on fact: the first three rooms are true and the grand pianos, and the Cucumber King filming the visiting teachers playing the pianos for his personal video collection. When I finally sat down to write a draft of the story, what struck me about the story, whether you like the Cucumber King or not, was his abject loneliness. At the time I was reading about how rapidly people were leaving Lithuania permanently. Bright young people. The “brain drain.” I thought: the Cucumber King is in this palace trying to build this business monopoly, and at the same time everyone has left. So I wrote it at a human level, of this person, not a very likable guy, but at the same time very strange.

Daiva: The Cucumber King is not the scariest character in the book. That belongs to two spiders. It’s called the “Spider Story,” and it will leave you not being able to sleep. The spider story, does that have any basis in truth? I keep thinking that there is something symbolic about the spiders.

Wendell: I don’t like spiders, personally. Actually that story is based on one of my earliest experiences in 1993. I was with APPLE in Birštonas and we were at an old Soviet sanatorium. In those times things were shut down, hot water was shut off, and my room was in shambles. The Red Army soldiers had damaged a lot of property on their way out of Lithuania. So I was in this room with a water closet and there were these spiders, everywhere, and I don’t like them, so I killed them, but two of them came back. I thought, “I can’t keep killing them like this,” so I let them live. They became like my family. The story is more complicated than that, but I think the notion I referenced in my introductory remarks is true: the human need to find home, to find a place that is familiar, that is comfortable, where one can see oneself in other people, is so important. It is a universal truth in my lifetime, but I think it’s also ages old.

Daiva: Another character that recurs in The Cucumber King of Kedainiai and In Lithuanian Wood is Paul Rood. When one thinks of Paul Rood, he is an American and visits Lithuania, and he’s called Paulius Rudis, but he is also someone who can be seen as a rude American. But then there’s the word itself. I asked my husband, who knows every word in the English language, the meaning, and he said R-O-O-D means a crucifix.

Wendell: As far as his name goes, I had very much in mind the crucifix and, in particular, an old English song called the “Dream of the Rood.” I certainly wanted to play up the rudeness, or crude behavior, his being an American and not knowing Lithuania’s ways. I also had in mind the color brown… I worked hard on his name, because I wanted it to be the right name.

Daiva: Now, in The Cucumber King of Kedainiai, Paul Rood goes missing, and we don’t know what happens to him. The woman who tells the story has this great line (her name is Goda). She says: “Why do people these days always want to know what happens after?” She is being interrogated. She is his landlady. So I want to ask you the same question, “Why do people always want to know what happens after?” Does this mean there will soon be another book where you are going to explain that?

Wendell: To me it’s not important what happens to him. The story is told as an interrogation. She’s answering questions for the police about his whereabouts and the more she tries to explain that she doesn’t know, the more they keep asking her, as in the old Soviet times. At the end of In Lithuanian Wood, Paul Rood decides to stay in Lithuania and to somehow make a living there. He decides to stay and becomes a kind of itinerant rascal. His love interest comes to Chicago, so they switch places. He wants to understand what he’s gotten himself into and who he is in terms of this new country, Lithuania. He wanders–he wanders into her life and he wanders out. But he is still around and I have plans for him down the road, because I think he is a person who I think can appreciate how, in our time, we can be global but at the same time local. We don’t all have to be assimilated into the global technological craziness of the world. We can still keep a personal place for ourselves. William Faulkner wrote about Jefferson County in many of his novels. He was called on this: You’re a Nobel Prize writer. Why don’t you write about more things? He didn’t feel he needed to write about anything else. He called Jefferson County, Mississippi, his “postage stamp of earth.” I see that as Lithuania. It is my postage stamp of earth. It has so much depth and breadth. I want Paul to come to that realization as a fictional character; he’s not there yet.

Daiva: I’m glad, because he is interesting. And the love story is one of the bright spots, though it doesn’t work out in a conventional way. The book, both books, there is something bleak about them. I think you do a superb job in creating a post-Soviet landscape. It’s almost a post-apocalyptic landscape. There are dogs running on the streets. There are lost children who appear and disappear. There is the sense of people really being lost. The men appear to me to be more lost – there’s the drinking, there’s Afghanistan – and the women seem to be sturdier.

Excerpt from “Spider Story” from The Cucumber King of Kėdainiai

by Wendell Mayo

When I reach the entrance of the school, I duck behind water cascading off the roof, sit on a brown brick half-wall to take weight off my ankle, and pause for a smoke. I go inside, investigate a small pile of loose mortar at my feet. Overnight, it has crumbled between seams in the slab ceiling and fallen, the usual: daily neglect, need. Each day I go to the school I spot some new sign of deterioration.

When I enter my classroom, students scatter, then sit, five in all, some with soiled hands from early-morning work in fields or kitchen gardens. I recognize Asta from the monkey bars, her overalls, sitting just behind Vytautas, Vyt as many call him, something of the class clown. Today we’re on the topic of family.

“Tell me something about your father, mother, a grandfather, or a grandmother,” I say.

Vyt’s arm shoots up, stiff, oddly angled at me, almost accusatory. He is a square-headed boy with a buzz-cut who without fail wears a mustardcolored muscle shirt and blue off-spec American jogging pants, each pant leg with a stripe that suddenly swerves inward at the kneecap. He is the first to raise his hand at every question I ask since, as he puts it, his long range ambition is to join the Police Academy in Vilnius, to be the “top cop.” He learns English from American television, cop shows in particular.

“All right, Vyt,” I say. “What is your father’s name?”

He pinches his face and glances at Asta. “Why do you want to know?

He is death.”

“You mean dead.”

“Yes, death.”

“All right, then tell me your mother’s name.”

“Death.”

“Aunts? Uncles?”

He slumps in his seat. “All death.”

“Then with whom do you live, Vyt?”

He shrugs his shoulders. “With you!” he says and smiles.

“Here? The school?” I ask and am hastily interrupted by Asta.

“No,” Asta says. “He lived at your sanatorium, ‘Spalio.’”

“Lives at the sanatorium,” I say.

“Lives,” Asta says shyly.

“Yeah, I lives there,” Vyt says and smiles at Asta. “Make my day, punk.”

Despite Vyt’s clever allusion to Sudden Impact, I’m also surprised that he’s been my companion at the sanatorium. No one in the school’s administration has mentioned it, though why should they? Like a surprising number of teens, Vyt must be an orphan, on his own, off the books.

At lunch hour I go outside, discouraged. What good is grammar? Is there some special syntax, some point of competency at which fresh mortar leaps into brick, fuel into furnaces, orphans into real homes? I think about quitting, going back to the States. A good smoke helps. I let the thought linger, fade. The day takes over, bright and blue. A stork passes over the school, headed for a farmer’s field and its huge twiggy nest atop a telephone pole. Near it, a roan horse stands harnessed to a hay wagon, its tail whipping lazily against its bright hindquarters—and there it is, all along, a wordless, beautiful transformational grammar like no other.

After my class, I reinstall myself in my room at the sanatorium, go into the water closet, and sit on the sharp, porcelain lip of the tub. I look down, see streaks of spider blood, my personal Rosetta Stone, notice more grout has fallen from the bath tiles and now rests in a perfect pyramidal pile near the drain. A few new filaments of spider silk stick to the debris. I look upward, don’t know why, suppose it’s because I’ve always thought life exists in twos—up, down; right, left; here, there—and so why not look upward to complete a picture of that which starts downward? There I discover a spindly nervous-footed daddy longlegs lodged near the ceiling, author of the new strands of silk. The longlegs is wire-thin. No wonder. The feeble filaments it’s spun can’t possibly hold prey. When I look down, I find another spider in the grout where the rim of the tub meets the wall. It’s fiercely at work on a thick, gray triangular-shaped web that funnels inward to where the spider itself sits, rather like a big dog in a house too small for it, its two front legs and pointed fangs hanging out. The dog spider is brown with thin red fuzz covering its thorax. Just behind its fangs, two large protrusions hang down, looking like miniature boxing gloves it rubs together to extrude and coil silk. Unlike the daddy longlegs’s strands, silken and clean, the dog-spider’s web is dull, thick, and filthy with desiccated bug shells, remnants of victims not caught by the stickiness of the web but by its hazardous surface geometry—pill bugs, flies, silverfish, all having “tripped” and fallen long enough for Bowser to scrabble out, inject its poison and drag them back into its doghouse for dinner.

As I sit on the toilet, my two spiders go about their constructions, the only survivors of the post-apocalyptic tub-scape I’ve created. They reestablish themselves with a kind of species defiance. I admire this. Let them live. Congratulate my magnanimous self by wandering the sanatorium, I suppose in search of Vyt.

Wendell: I can say that, as far as the men and the women, I saw what had happened. The women were a pillar of stability in those old days, right after independence. And through no fault of the men. So many of them were in concentration camps. At one point I had to go to a hospital to have my eyes checked; I have high blood pressure and at the time had blood vessels bursting in my eyes. I had one specialist check me out, and I had another and another, and they were all women. All the doctors were women. Maryte, a friend who served in the kitchen while I was with APPLE, had an advanced degree in biochemistry. What a waste! These beautiful people! I’m hoping, I’m sure, it has changed now.

Daiva: The absence of men, I think is a theme echoed in another great story from the new book called “Cold-Fried Pike,” where the daughter tells her father, who is visiting from, I’m assuming the United States, “It’s not often we have a man visit.” I’m wondering if you could talk a little about that story.

Wendell: I tend to be a collagist; I borrow different things and try to put them together in one story. That story is made of several pieces. One of my interpreters from my APPLE days invited me to visit her family in the Pašilaičiai District of Vilnius. When I got there it was three generations of women who were the family. They said there were no men in the immediate family anymore. We proceeded to have dinner, and the interpreter had insisted that I bring cold fried pike because that is what her grandmother liked, so I got the pike. You know, you can buy it stores. I also brought a bottle of Bulgarian wine. Each woman–the daughter, the mother, and the grandmother–began to tell me three different narratives stemming from the grandmother’s narrative, how she used to fish with her father and catch pike in the old days during the Second World War. What struck me was that the three generations of women had completely different narratives.

The other thing I was working with, since I’m interested in folklore, was “Little Red Riding Hood,” which is also called “Little Red Cap.” While in Vilnius, the winters are rough, so I got this red wool cap that I wore all the time and I sort of fancied myself as going to visit “grandma.” I got on the trolley in my little red cap. I changed trolleys at the milk factory. All to go to “grandma’s house.” A lot of the story is true, but I wanted to get across a sense that determining family histories is a communal mission. It’s a jungle. It’s hard. At one point, my wife’s family asked me if I could find their roots. So I went to Alytus. From there I went south and asked as best I could in my bad Lithuanian, where the graveyards are, and looked for the names on the gravestones, for ‘Masionis.’ And I had some people tell me, “Well, no, they’re south of here, and don’t you know they may have lived in Poland?” I was all over the map trying to find this. And so I think that that story, when I finished it, helped me understand and appreciate just how necessary it is to find one’s origins, but at the same time how difficult it can be.

Daiva: Your grasp of Lithuanian is remarkable. You get the expressions right. You get the songs right. I’m wondering whether this is because of your sharp ear as a writer or whether you had a little bit of help.

Wendell: I listen a lot. I love the sound of words. I purposely, especially in In Lithuanian Wood, wove in Lithuanian language because language is culture. Lithuanian is a hard language to learn, but it is so pure. It is really beautiful. When I was living in Vilnius, 2001-2002, I was teaching at the university. And since I was there, I was practicing my Lithuanian. It was hard to practice in the restaurants, banks, and the like because so many people there want to know English. I would say something in Lithuanian, and they would say, “Let’s speak English” and I would say, “No, I don’t want to speak English.” One time I was making an appointment to meet someone in Kaunas–another writer–and I was on the telephone with her. I was speaking in Lithuanian and I didn’t think anything of it. One of the other faculty members in the English Philology Department came up to me afterwards and said, “I’m sorry. I was eavesdropping. I understood everything you said in Lithuanian perfectly.” I said, “Really?” and she said, “Yes, you made an appointment at this time in Kaunas…” I was shocked. I didn’t think I was that good. I had my high point. I had my peak. I was so proud of myself. But it’s gonefrom me, and I envy the fact that so many Lithuanian-Americans had language education in Saturday schools. I really envy that.

Daiva: One of the questions I think about when I read your work is why aren’t you more famous? I have certainly seen writers who are not half as good get a lot of press and that makes me sad. How do you react to that?

Wendell: I don’t write for popularity. I write to understand myself and the world around me. I think the best part of writing is getting the experiences necessary to come to a point where I think I can be honest with myself and honest with others, too. Because I’m a short story writer, I’m interested in histories of the human heart. I think people are important. I think individuals are important. If I get more readers, that’s fine.

Because I’m a story writer, I will tell you a little story about changes in Lithuania. When I was staying in Vilnius, I lived near the Town Hall. This was in 2000. In order to shop I had to walk down Vokiečių gatvė and up Naugarduko to Maxima’s. I’d fill up my book bag with Diet Coke. So I would have to carry all this liquid in the dead of winter. I would walk up Naugarduko, which was steep, in the snow, and after a while I started feeling proud that I could do this. I would get my exercise. So for that entire winter I was thinking, “I’m this rugged Lithuanian guy.” So what happens? In early summer, the week I leave, they open a new Rimi’s in Old Town, only one minute from my flat! So I think the changes I’ve seen are commercialization. So many cars. But seriously, I’m worried about the environment. I’m worried about the Mažeikiai refinery, the Cucumber Kings of the world. I worry that the notion of free enterprise, free people may be taken advantage of by monopolies. On the other hand, it’s nice to walk one block to buy my groceries! But I have to tell you I was proud of myself. People in Lithuania walk all the time; I couldn’t keep up with them. Every so often they would look back and say, “Are you coming or not?”

Question from the audience: Do you have a favorite place in Lithuania?

Wendell: My favorite place of all time is Merkinė, on the way to Druskininkai. There is hill fort and it overlooks the conjunction of two rivers and there is a farm there. It’s like the Tigris and the Euphrates. I hope it never gets spoiled.

I can just sit there and gasp for just hours at the beauty of the place. Kernavė is also very beautiful. There is a kind of timelessness of the hill forts and the natural beauty in those kinds of places. My second favorite place is Nida. I like hanging out at the beach. But I actually prefer the Kuršių Marios side to the Baltic side. I’ve never been to Kėdainiai. I heard the story in detail from Vaiva and that’s all I needed. But of the stories I’ve written, I’ve been to 95% of the places where the stories take place.

DRAUGAS NEWS Lithuanian World Wide News in English

DRAUGAS NEWS Lithuanian World Wide News in English