By GEDIMINAS INDREIKA.

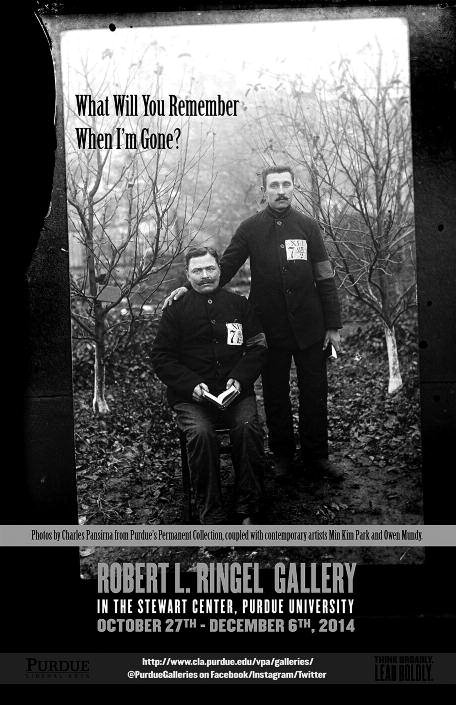

The exhibit at Purdue University’s Robert L. Ringel GalleryWhat Will You Remember When I’m Gone (October 27 to December 6, 2014) offers a rare glimpse into the work of Charles Pansirna, a distinguished Lithuanian-American photographer. The exhibit also displays contemporary photographs by Owen Mundy, though primarily military portraits as a complement and counterpoint to the subject of pride and tradition. Charles Pansirna’s images reveal a cross-section of everyday life in Chicago’s Lithuanian community at a time when family bonds, ethnic identity and religious values were strong.

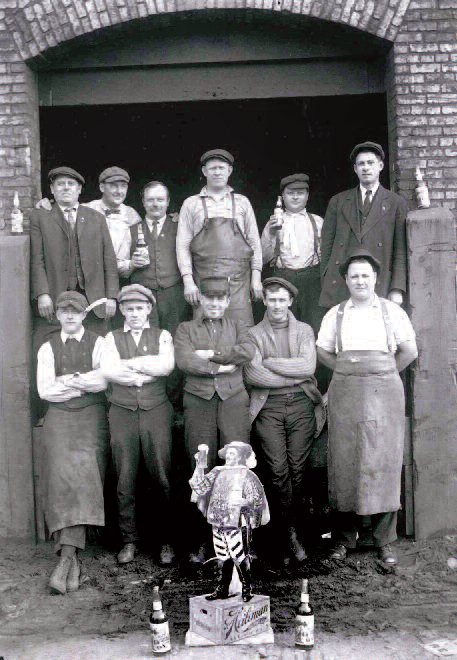

Pansirna opened a photo studio near 18th and Halsted Streets in 1914 in the neighborhood now known as Pilsen. Pansirna (1888-1970) was not merely a studio photographer, but he also was an avid chronicler of community-centered events – picnics, funerals, and the annual carnival at the Providence of God Lithuanian Parish. The greater part of Pansirna’s collection – some 1500 negatives and photographs – is now housed at Purdue University Galleries. They are mostly studio portraits and family pictures. There are also photos of rites of passage: First Communions, weddings, and group photographs of school children and sports teams.

‘’Look, we have arrived!”

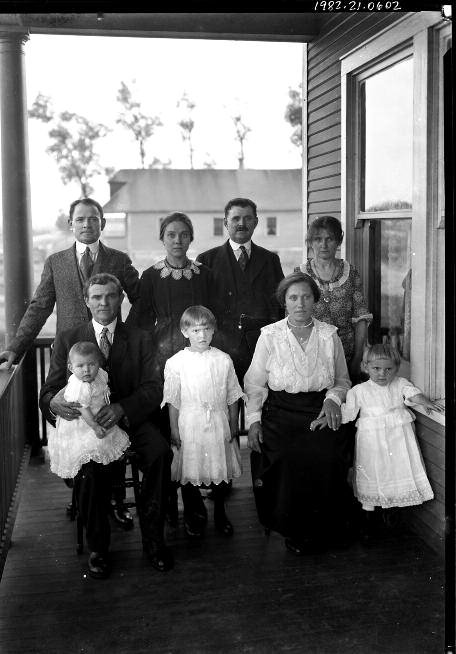

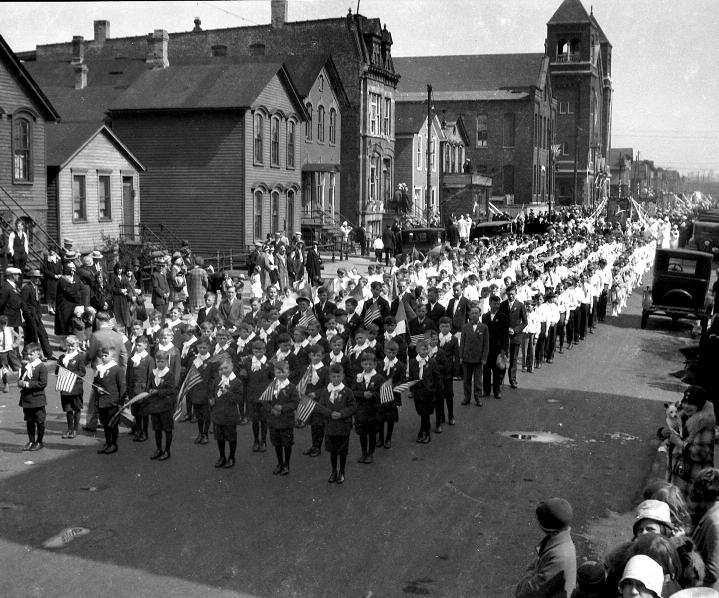

As a social observer, Pansirna successfully emulated Norman Rockwell’s approach in recording Chicago life through his photographs. There are interior shots of grocery stores, taverns, barber shops, and unique views of church processions and street vendors in the 18th Street neighborhood. Then there are enlistment photos of soldiers in uniform. Several photographs demonstrate the social mobility that Lithuanians had attained at that time: the family proudly poses in front of a newly constructed house, which they have acquired. Pansirna’s signature on a photograph was indicative of attaining a higher status. Families proudly displayed these photos on their china cabinets or hung them on their living room walls.

Most intriguing are the funeral photographs. They typically showed an open casket with the bereaved family members standing by. The photographs speak volumes about Lithuanian-American funeral traditions. The deceased’s name and the date of the funeral etched on the print is an invaluable resourcefor Lithuanian genealogy research.

Pansirna’s name was little known in the social circles of post World War II Lithuanian immigrants. This can in part be attributed to the closure of his studio circa 1953. After he retired, Pansirna receded into obscurity, although he continued to organize select samples of his work into an archive.

The exhibit at Purdue is curated by Rosanne Altstatt and Michel Hathaway and is supported with research conducted by the students in the Honors College class “Photography and Cultural Value.” The Purdue students examined what is seen in the Pansirna photographs, and some of their comments are posted next to them. In the photo of two men ( possibly brothers?) in the woods, both are wearing black arm bands, signifying mourning. One is holding an opened prayer book. Can we unlock the secret of whom it is that they are mourning?

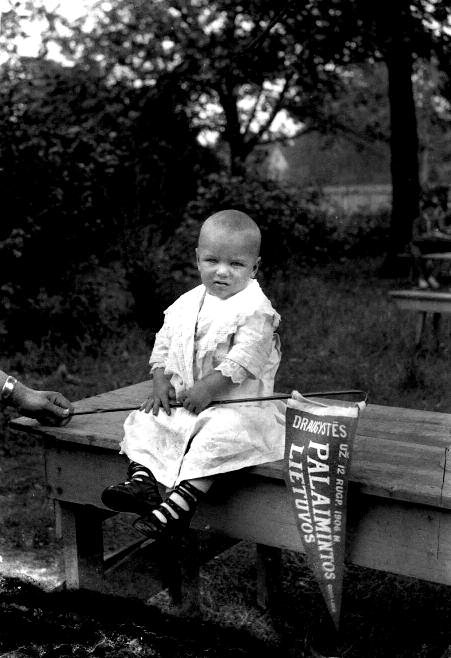

In another photograph, a child sitting on a bench is holding a pennant which reads “Draugystės Palaimintos Lietuvos” and is dated 1906 (Society of Blessed Lithuania, c. 1906). The student’s comments note that the child’s shoes are Edwardian style, but he most likely was mistaken by identifying it as dating from 1906. Looking up Aleksas Ambrose’s book History of Chicago’s Lithuanians, one finds that this charitable organization was organized in 1906, before Pansirna had even settled in Chicago. In 1920 the Society of Blessed Lithuania participated in a demonstration protesting the Polish occupation of Vilnius, and raised funds to aid Lithuanians in Vilnius. The photograph was most likely taken at a picnic in the 1920’s.

I first learned of Pansirna from an article by Ed Lapinskas in “Protėviai,” a bulletin published in 2007 by the Lithuanian Global Genealogical Society. Ed Lapinskas, Pansirna’s nephew, remembers his uncle as having a reserved personality, one who avoided carousing and parties and generally maintained a healthy lifestyle.

Charles (Karolis) Pansirna was born in Betygala, Lithuania. He immigrated to the United States around 1907. Working in the coal mines of Pennsylvania, he saved enough money to move in 1915 to Chicago. Having the rare gift of talent and through hard work, he acquired photographic skills on his own. Pansirna died in 1970, and is buried together with his wife Sophia in St. Casimir’s Lithuanian Cemetery in Chicago.

A scholarly study of Pansirna’s photographs of Lithuanian-Americans is long overdue. Many of the funeral images that identify the person portrayed can be cross-referenced with the records maintained at Chicago’s St. Casimir Lithuanian Cemetery. Pansirna’s photographs are deposited at various other institutions and in private collections as well. They are not properly catalogued. The M.K. Čiurlionis National Art Museum in Kaunas holds at least a dozen of Pansirna’s originals. Many aspects of our hidden history are still waiting to be studied and their secrets discovered.

A scholarly study of Pansirna’s photographs of Lithuanian-Americans is long overdue. Many of the funeral images that identify the person portrayed can be cross-referenced with the records maintained at Chicago’s St. Casimir Lithuanian Cemetery. Pansirna’s photographs are deposited at various other institutions and in private collections as well. They are not properly catalogued. The M.K. Čiurlionis National Art Museum in Kaunas holds at least a dozen of Pansirna’s originals. Many aspects of our hidden history are still waiting to be studied and their secrets discovered.

DRAUGAS NEWS Lithuanian World Wide News in English

DRAUGAS NEWS Lithuanian World Wide News in English