By TADDES KORRIS.

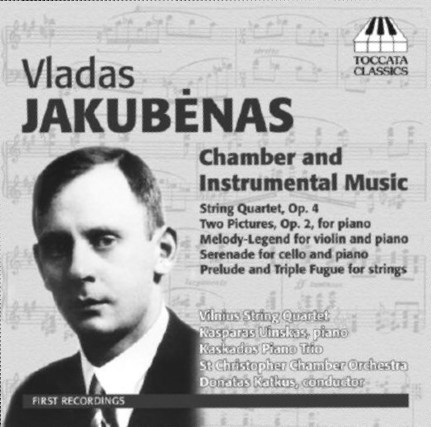

The name of Vladas Jakubėnas is one of great importance in Lithuanian musical and cultural history. His creative work took shape during the ’20s and ’30s, when Europe was bustling with new ideas in art, technology, psychology and ideology. Lithuania, a free state since 1918, was defined by its idealism and openness, where creativity and freedom manifested itself amongst the ripe feelings of national identity. Jakubėnas embodied this spirit throughout his life in Latvia, Lithuania, Germany and the United States. Like many Lithuanians, he was forced to leave Lithuania in 1944 and much of his artistic energies were extinguished as a result. He still left a powerful impact on Lithuanian culture, composed a large number of excellent works and developed a significant reputation in Germany, Lithuania and the United States. Many readers may even recognize his name from arrangements for song and dance festivals, where he left another prominent impact that is still heard today.

Vladas Jakubėnas was born in Biržai on May 15, 1904 to a Protestant family. This was unusual in a predominantly Catholic Lithuania, yet the town was an important center for the Reformation back in the 16th century. In fact, Jakubėnas’ father was a minister and superintendent of the Lithuanian Protestant Reformed Church. After a conservative education with a great deal of musical training, Jakubėnas chose to study in Riga, Latvia, where Protestantism was the accepted faith. Unlike many composers who were discouraged by their parents in pursuing musical study, Jakubėnas was warmly encouraged to pursue his musical talents. He arrived at the Riga Conservatory in 1926 where he studied both piano performance and composition. Notably, his composition teacher was Jazeps Vitols, a student of the famous Rimsky-Korsakov. It is in St.Petersburg where Vitols established himself as a very famous figure in Europe, well respected for his compositions, pedagogical talents and critique. It is most likely from Vitols that Jakubėnas strengthened his understanding and use of Lithuanian folk music. Vitols himself used many Latvian folk sources in his music.

After completing studies in Riga, Jakubėnas received a scholarship from the Lithuanian Education Ministry and was accepted to the prestigious Berlin State Academy of Music, one of Europe’s finest institutions at the time. From 1928-1932, Jakubėnas focused solely on composition. He was accepted to study with the famed Franz Schreker, a prominent Austrian operatic and orchestral composer. Jakubėnas experienced many modernistic trends in art, music and literature at this time. The cosmopolitan artistic environment in Berlin and progressive attitudes in Germany were among the most interesting in history.

It is in Berlin that he developed a significant reputation as a composer who was well respected by his professors and colleagues. Jakubėnas’ music was imbued with modernistic tendencies, experimenting with many techniques, sounds and combinations. Though by today’s standards, it would be deemed fairly conservative, it was incredibly inventive for the time. His music became quite popular and was widely performed, considering he was a relative newcomer to Berlin. Many of his most famous works like the String Quartet and Symphony No. 1 were premiered at the famed International Society for Contemporary Music at various concerts. Franz Schreker conducted the premiere of the Symphony No. 1 with the Berlin Radio Symphony.

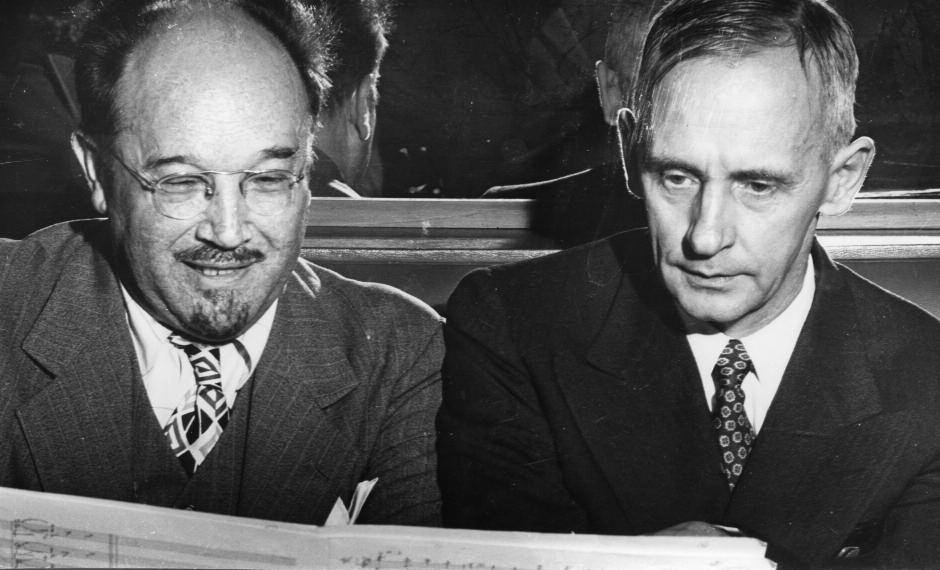

As his popularity grew and his works reached audiences, Jakubėnas was nicknamed “The Lithuanian Hindemith.” For reference, Paul Hindemith was one of Germany’s (and the world’s) most prominent contemporary composers who developed a unique modern language. By the 1930’s Hindemith had already developed the musical language he would be best known for, where he would freely modulate between all 12 notes in the chromatic scale, ranking the intervals and chords from most consonant to most dissonant. His music is marked with brevity and a powerful contrapuntal texture. Interestingly enough, this language was considered “neoclassical,” created by looking back at the 17th and 18th centuries in terms of form and structure. With this in mind, being nicknamed the “Lithuanian Hindemith” was quite the compliment for a young Lithuanian composer!

As his popularity grew and his works reached audiences, Jakubėnas was nicknamed “The Lithuanian Hindemith.” For reference, Paul Hindemith was one of Germany’s (and the world’s) most prominent contemporary composers who developed a unique modern language. By the 1930’s Hindemith had already developed the musical language he would be best known for, where he would freely modulate between all 12 notes in the chromatic scale, ranking the intervals and chords from most consonant to most dissonant. His music is marked with brevity and a powerful contrapuntal texture. Interestingly enough, this language was considered “neoclassical,” created by looking back at the 17th and 18th centuries in terms of form and structure. With this in mind, being nicknamed the “Lithuanian Hindemith” was quite the compliment for a young Lithuanian composer!

Upon Jakubėnas’ return to Lithuania in 1932, most of his works written at home tended to be less overtly modern than they had been in Berlin. Jakubėnas said that his moderate musical language of this time was like Lithuania itself, “a remote and lyrical place.” He was quoted, “Lithuania is not a country of huge cities: just stroll to the outskirts of Kaunas or take a half-hour ride on a bus, and we’re steeped in completely rural, quiet, romantic country.” In this case, it is interesting to consider if Jakubėnas sacrificed certain parts of his creative voice simply to be more accessible. Lithuanian audiences would have certainly been less inviting of the avantgarde tendencies that were commonplace in Germany. Though often debated, his mature romantic style upon returning to Lithuania was much different from the more naive music of his early days in Latvia.

One can hear trends of impressionistic coloring, akin to the works of Debussy and Ravel. This was a common trend among many Lithuanian composers of the time. That being said, Jakubėnas’ tonal palate and harmonies were distinctly his and very sophisticated. He wrote a significant amount of music in Lithuania, including his Symphony No. 2, Symphony No. 3, Serenade for Cello, and Rhapsody for Orchestra. He had tremendous success and was a major part of Lithuanian concert programming at this time. He also took a post as professor at the Kaunas conservatory which he held until 1944, teaching both composition and piano. It is in Kaunas that he also began publishing numerous periodicals on music and became Lithuania’s most acclaimed music critic. He published extensively on his Berlin days, describing and analyzing many of the important musical and artistic trends.

Sadly, with Lithuania’s annexation into the Soviet Union, Jakubėnas left his homeland for Germany in 1944. Still commanding a fairly significant name in Germany, he was able to continue his work as a professor and critic during and after the war. It wasn’t until 1949 that he decided to emigrate to the United States. In the ashes of Europe, he also left behind a part of his creative soul, just as so many prominent composers did. Much like the Russian Composer Rachmaninov who left Russia before the 1917 Revolution, Jakubėnas composed very little in the United States. Though he was not impoverished by any means and actually led a fairly comfortable life in Chicago, he mostly edited musical journals, published articles and continued his work as a critic. Musically, he spent his time editing many of his old works and making choir arrangements for song and dance festivals. Jakubėnas’ creative energy was a shadow of its former self, which was fresh, colorful and optimistic. His reputation in Chicago was well established before arriving, as his Symphony No. 1 had been performed by the Chicago Symphony in 1933, followed by subsequent chamber performances of his works later on. He was an organizer and pianist for the U.S. and Canadian song festivals in 1956 and 1961. Many of the songs performed at those festivals were ones arranged and composed by him based on Lithuanian poetry new and old, and are still performed today. A theme that predominated in his American period was the emigrant’s longing for his homeland, amidst a backdrop of autumn, longing for death.

Jakubėnas composed three symphonies, a ballet titled Vaiva, four cantatas, 60 songs, seven chamber works and 13 solo piano pieces. Though not a particularly sizable output, it is important to note nearly all of these works are from 1926-1944. Were it not for the circumstances of World War II, it is likely he would have continued to compose with the same fervor as in his youth. But, like so many artists, when they lose the fundamental key to their expression and identity, it is hard to find the will to create. When the most beautiful muse is your homeland, the source of your language, expression and culture, being bereft of it is painfully debilitating. Fortunately, he and his music represent a snapshot of Lithuania’s best at a time where prosperity, freedom and individuality were at their strongest. It is this Lithuanian spirit that asserted itself fifty years later that led the revolutions and reforms to regain independence.

DRAUGAS NEWS Lithuanian World Wide News in English

DRAUGAS NEWS Lithuanian World Wide News in English