An interview with author Felicia Prekeris Brown

By Danutė Januta.

seventy years have gone by since the great exodus of Lithuanians, Latvians, and estonians fleeing their countries during World War ii to escape the return of soviet occupiers. this period of history will be commemorated in the Balzekas Museum’s Baltic“dP”displaced Persons exhibit,scheduled to open in Chicago on august 23, 2014.

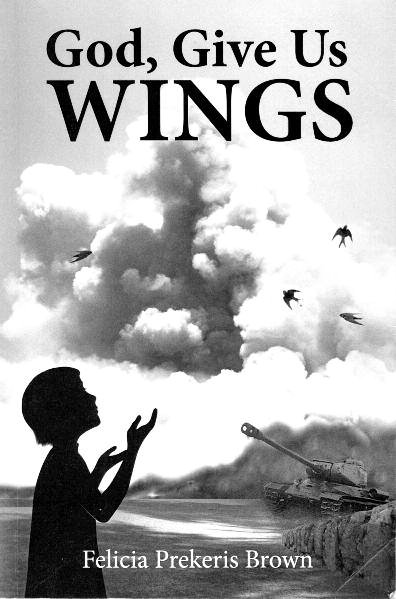

As if purposely timed to coincide with the exhibit comes Felicia Prekeris Brown’s memoir, God, GiveUs Wings, which recountsthe story of her family’s struggles to maintain a normal life under the ruthless dictatorships of stalin and hitler, and their last-minute flight from Lithuania to avoid the returning soviets and certain exile to siberia. starting with the day in 1939 when hitler reclaimed Lithuania Minor for germany, and ending in early 1952 as her family sailsinto newYork harbor,she detailsthe life of typical Lithuanian civilians whom the political leaders ofthe day viewed as mere collateral damage in their battles for domination.

When the war finally ends in May 1945, after narrowly avoiding repatriation back to Lithuania,the family issettled in a displaced Persons camp in the german British Zone. after years of living in limbo, the family finds a temporary home in england, and finally attains its goal: life in america.

God, Give Us Wings tells a story similar to that of thousands of other refugeesfrom the Baltic nations, but in way which balancesthe troubles,sadness, hunger, and pain of exile with examples ofselfless help, generosity and timely advice,touching on the worst and the best traits of humanity. the author—a mere child during the events—makes palpable the fear of her oldersister and the confusion of her parents, whose love and dedication to each other prevailed over the perils around them.

Danutė Januta, of Berkeley, California, recently interviewed the author, whom she has known for almost 40 years, on behalf of draugas news.

Felicia, how did you come up with the title for your book — God, Give us Wings?

Imagine a warm spring day, late April 1945, in Germany. I’m 8 years old. The confusion and noise of the war as it draws to its end pervades my world. Standing outside, I see clouds of black smoke rising in the southeast. German tanks and military vehicles of every description choke the roads and byways. An ever-increasing number of American, British, and Russian bombers roar overhead.

Nazi officials have taken away my beloved father to dig anti-tank trenches; my mother and sister are assigned to work in a military field kitchen. Mother keeps repeating that, living in the midst of a German battalion, we three will certainly die when the approaching battle lines reach us.

Suddenly I notice barn swallows looping in the air above the farm, so free, so safe from harm. “God, give us wings,” I pray, seeing flight as the only way to escape the destruction awaiting us on the ground. But even as I pray, I know that such a physical miracle is not possible, not even for God. And yet, we did escape, on the wings of hope, love, and courage.

You were seven when your family, one among hundreds of thousands from the Baltic countries, fled Lithuania. How could you remember so far back?

One remembers best what was most deeply felt. The events I describe as coming from my own memory were so traumatic, so vivid or unusual, that to this day I recall almost every detail. Both the painful times and the joyful. Of course, the dialogs are pure approximations.

However, most of my book is based on the stories told by my parents and my older sister Milda. I had so much material that at first it overwhelmedme. I had kept all the documents that had not been lost or thrown away,I had a notebook of written reminiscences from Mother and Father, and I still had letters exchanged by my parents during a long separation. I also had an envelope full of miscellaneous notes,the jotted conversations with Milda during her last months of life.

Most importantly, I had repeatedly tape-recorded their recollections.

Did you also have photographs?

We had very few from Lithuania, because everything we owned was lost in a bombing raid in July 1944. However, some weeks before that disaster, when Mother, Milda, and I had left Vilnius for the safety of a distant farm, my sentimental sister had taken her personal album with her. Later, she had to abandon the album, but she removed handfuls of photographs, and managed to protectthem, in a deeppocket of her coat, through all the troubles and trials of our flight. They connected her to a past she cherished. I made copies of most of them in later years.

I did have quite a few pictures from the DP camps, which served to revive many fading memories.

What gave you the impetus to start writing?

At the age of 74, I found myself overcome with feelings of shame and dread. Years before, I had repeatedly promised my parents and Milda that I would write down the story of our difficult lives during that tumultuous era in European history, and I had failed to deliver. One day, I noticed that it was becoming harder to remember the flow of events. I worried that I would not have the time and patience to revive 13 eventful years on paper.

My wonderful sister had died at age 75. My father had died on his 75th birthday. Was my expiration date looming? If I were to live up to my promise, I had to get going.

There was additional motivation: my son and grandson, and my sister’s children and grandchildren. Someday, I knew, they would be curious about the reasons why their roots had been transplanted to the USA. I had an obligation.

How did you begin? Did you make an outline?

I had no idea how to begin! I had written hundreds of reports during my working years, but typically, none longer than five to ten pages. I felt paralyzed. Luckily, a dear friend, author Evelyn Cole, came to my rescue. She gave me two tips: first, determine who your audience is and write for it. Second, follow what writer Ray Bradbury advised: “First throw up, then clean up”—meaning write it down as it comes to you and don’t worry about spelling, sentence structure, or style. You can summon your inner critic after you’ve corralled the materials.

Whom did you envision as your audience?

I started with my son in mind, but found that I was putting down so many details about ancestors and family members that I was yawning with boredom when I reviewed what I had written. Instead of heading for my goal—to tell the story of our struggles as civilians trapped in war—I was producing a genealogy.

I scrapped most of it, and wrote visualizing Evelyn as the reader instead, seeing her as a typical American unfamiliar with the history of the Baltic States and the ruin Stalin and Hitler wreaked upon them. I needed to give her enough historical background to provide a context to our family’s flight to freedom; I had to speak of my parents’ past to draw a foundation for their character and their reactions during times of stress.

Were there any stumbling blocks? Did writing the memoir revive bad memories?

Felicia: You’ve hit the nail on the head. There were incidents that I cringed to remember. At first, some episodes I simply omitted. In others, I averted the pain by confining them to a short summary. It was when I asked my son Algis to proofread the book that he literally shamed me into facing events as they had occurred and setting them down in detail.

Can you give us an example?

The worst one for me was witnessing my father being dragged to his death—or so we thought—by our runaway horse. But let me explain a little.

As we were fleeing from Lithuania, my father exchanged a bottle of homemade moonshine for a huge, tired-out cavalry horse. Shortly thereafter, in Prussia, we found an abandoned one-horse supply cart. The shafts of the cart were too short for the foultempered mare, plus she was not used to pulling anything behind her.It spooked her. But it was transportation, and better than walking.

One dreary morning in November 1944, we came to a hilly section in Poland, then still under German control. The mare was giving Father a lot of trouble, so he wrapped the reins tight around his wrists to exert more control. But as the road descended, the singletree (the part of the harness to which the traces are attached) kept hitting the mare’s rear legs, and suddenly she bolted, racing as if on a cavalry charge.

The top part of the little cart, with Mother, Milda, and me in it, broke off the axles and wentflying backwards, scattering us all over the road. Father, who was sitting on the driver’s board in front, was flung forward to the ground, on his knees and stomach, his head mere inches from the vicious hooves of the mare. As we watched his body dragged down the hill, bouncing on the road between the wheels, we were absolutely convinced that, when the horse finally stopped, we would find Father dead.

Miraculously—he survived. To this day, when I see anyone, even a baby, fall flat on the ground, my heart starts to race in terror.

The story of your flight is especially harrowing. Why did your family wait till the last minute to leave?

We certainly could have left earlier by train. The problem was Mother. She did not want to go far from everything she knew and loved. Like most Lithuanians, she was sure the USA and Britain would restore Lithuania’s independence as soon as the war ended, and clearly it was going to end soon. The farthest she was willing to go was into Prussia (now Kaliningrad). And when Mother made up her mind, her decision was chiseled in marble.

Mother loved and admired Father—his education, good nature, and charm She was very proud to be his wife. But she did not listen to him.In her opinion, he was too easy going and impractical. On the other hand, she listened to mere acquaintances if they impressed her as being astute and cunning. In fact, we got out of Prussia only because such a family crossed our path and asked us to go to Berlin with them—they spoke no German and needed Father to translate. She sounds formidable! Oh, she was. Father’s character was simple compared to Mother’s. He was the ultimate “good person,” who would not hurt anyone even if he had to put his family at risk. He was an optimist who trusted that things would work out if he acted according to his conscience. Mother was the practical one, who saw her role as our protector no matter the cost to herself. Under her sometimes-harsh demeanor, there beat a tender, yearning heart, enamored of music and romance. But during her bleak childhood, she had learned to struggle, endure, and survive, whereas Father had always had parents and siblings to smooth his way.

During our flight from Lithuania, if we had no food, Mother would go begging, even though she despised doing it. Later, in the DP camp, when provisions were so reduced that Father was fading away, she made Milda go with her to England to work as maids. They scrounged and saved every penny, and sent back things like thermos bottles, which Father could barter with the Germans for food. She did what she had to do to keep her husband and daughters alive, but sometimes it cost her lasting emotional pain. She grieved over one particular incident to her dying day.

What incident was that? Did you describe it in the book?

Yes, it’s in the book. I, too, cannot erase it from my mind.

It was in the early autumn of 1943, a drizzly day in Vilnius, and Mother had kept me home from school because Ifelt unwell. There was a rapping atthe front door. I rushed to cling to Mother, having learned that unexpected visitors were to be feared. Cautiously, Mother opened the door. Before us stood a little girl: anxious, big brown eyes, prominent cheekbones, her head wrapped in a “babushka” scarf. Her thin wrists stuck out of frayed coat sleeves that she had long outgrown. Her knees looked big and red above her stick-like legs. She opened a small empty bag, like a child’s pillowcase, and said in Polish that she was very hungry and could we spare some bread? Mother answered in Lithuanian, butthe child shook her head that she didn’t understand. Mother carried a grudge against the Polish population, who had stolen Vilnius from us and still refused to acknowledge that it belonged to Lithuania. She started to tell the girl to go ask from her own people, but I intervened. Knowing how hunger hurts, I asked Mother to give her my share. Perhaps I made her feel ashamed, because she came back with a big piece of bread and a chunk of dried Lithuanian cheese.

The little girl’s face lit up. She tried to kiss Mother’s hand, and then clasped her thighs in a tight hug. Mother bent down toward her, and the girl suddenly said, “Lady, dear angel, please can you save me?”

Mother later said thatit was as if a light bulb had gone on: this was no Polish beggar, this child was Jewish! How had she managed to slip away from the ghetto? What kind of horrors were going on there, that parents would send out their little ones alone into the cold, threatening streets in hopes that some stranger would save them from the Nazis? And what should she do? The Germans had made it clear that to help the Jews was treason, that the whole family would be instantly condemned to share their fate. She had to think of her own two young ones—she had to say “No.”

The little girl left, thanking us for the food. Mother collapsed, crying her eyes out. Years later, I learned that she and Father discussed this incident over and over. Father did not think he could have refused a small child’s desperate plea. Because no child from the ghetto ever came again, neither of them was put to the test. But to her dying day, Mother wondered if she had done the right thing, and prayed that some braver person than she had offered the child refuge.

The experiences of those bitter years had consequences for everyone who lived through them. Did they leave lasting scars on you and your family?

You know the famous quote, “What does not kill you, makes you stronger.” It worked for me because I was a child who believed in miracles, and despite evidence to the contrary, still felt that my parents would magically protect me from harm. Throughout my life, when faced with painful situations, deep inside I felt I would somehow prevail.

It did not work for Milda. The years of fear and panic were too much for a teenager who knew, as I did not, that our parents were floundering, and ultimately incapable of saving us from hunger or bombs,the Soviets, and Siberia. Dread ate a black hole in her psyche. While she was young, she was able to repress the past and live a happy life. When she was about forty, and unexpected troubles hit, she fell apart. Panic attacks assailed her. She could neither leave the house, nor spend nights alone. Fortunately, she had a helpful family to support her, plus medications, and her love for people kept her involved and cheerful. But I still think it was the anxiety gnawing away inside that caused her early death.

The privations of war were responsible, I’m sure, for Father’s premature death. He had developed pernicious anemia, which was misdiagnosed and treated with harsh chemicals in the DP camp. His digestion was forever impaired, and he died of stomach cancer. But emotionally, the war years had made him more forgiving and kinder than ever. He focused on the help and compassion that strangers had given us along the way, and never failed to muse about the mystery of God’s ways: why had we been saved when so many others had perished?

As for Mother, she had done all she could to protect her family, and she grew stronger knowing she had succeeded. She mellowed with age, and loved to read classic Lithuanian poets like Maironis. For the last 25 years of her life, she lived with my husband and me. Cancer got her too, but she was close to 98.

What of your relatives in Lithuania? Did they survive, and when did you reestablish contacts?

The Soviets did send one cousin to a work camp in Kazakhstan, but the rest escaped deportation. Notlong after Stalin’s death, around 1955, we received a very short note from Mother’s niece, indicating that my elderly grandmother, and all the maternal relatives, had survived the war.I have no words to describe the joy that the news caused Mother. In fact, little by little, we heard from everyone, and I keep in touch with most of them to this day, thanks to email!

I admit that your story was emotionally gripping, and sometimes I got through a particular scene only by remembering that here you were, safe and sound, and that all four of you eventually led a happy life in the USA. Where can one buy your book?

God, Give Us Wings can be purchased through Amazon.com or ordered through a bookstore. I am pleased by the extremely positive reception among American readers. People have commented that they had no idea of the cruelty and destruction perpetrated by the Soviets—US allies during the war—in the lands they occupied. I feel as if I’ve done my part to promote the history of Lithuania.

Thank you, Felicia!

It has been my pleasure!

DRAUGAS NEWS Lithuanian World Wide News in English

DRAUGAS NEWS Lithuanian World Wide News in English