By RIMAS ČERNIUS.

“No Home To Go To” was developed by the Balzekas Museum of Lithuanian Culture in collaboration with the Chicago Estonian House, the Latvian Folk Art Museum, and the Lithuanian Emigration Institute of Vytautas Magnus University in Kaunas, Lithuania.

On August 24, 2014, the Balzekas Museum of Lithuanian Culture opened a new exhibit entitled “No Home to Go To – The Story of Baltic Displaced Persons, 1944-1952.” The exhibit calls attention to a segment of 20th century history that is often forgotten or suppressed – the story of thousands of refugees from the Baltic countries who fled to the West as Russian Communists occupied their homelands in the waning days of the Second World War.

President Franklin Roosevelt once referred to the United States of America as a nation of immigrants. Those of us Americans who trace our heritage to the Baltic countries of Lithuania, Latvia or Estonia, know that the path to America was a hard one for our immigrant parents and grandparents. However, many of us are not aware of the details of daily life of Baltic refugees in German refugee camps after the Second World War. The exhibit at the Balzekas Museum gives us a vivid picture of what our parents or grandparents went through after the war. Perhaps it is even more important as a documented testimonial to the desire for freedom that motivated thousands to flee from Russian Communism. For many this was a risky flight into the unknown,but it was a risk that thousands of Baltic people were willing to take in the hope of finding a place where they could live in freedom.

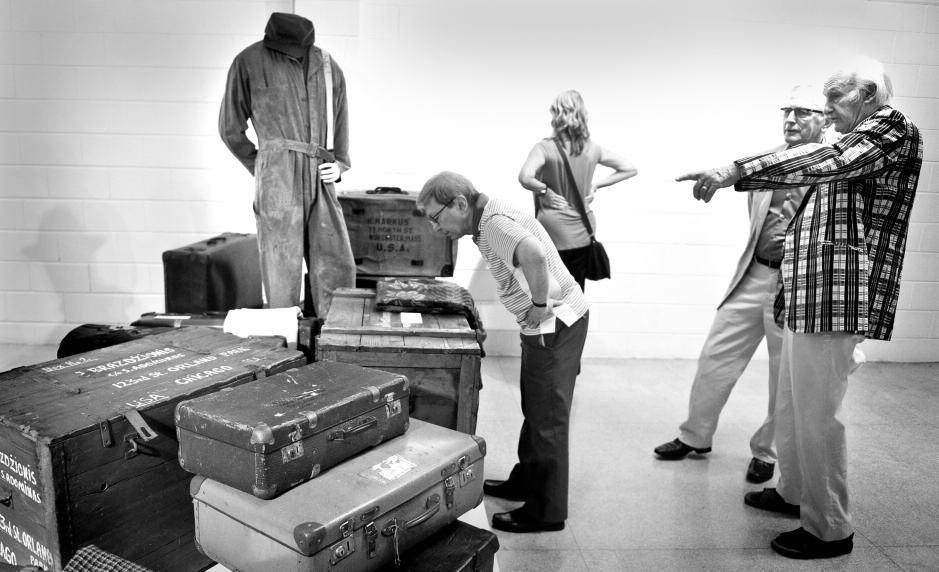

As you walk into the exhibit, you are greeted with a pile of suitcases and trunks – a symbol of the refugee experience. Each refugee family which succeeded in getting permission to emigrate to the United States took with them what few possessions they were able to obtain and pack into containers. In many cases, the “displaced persons” who came to the United States had to start from scratch, with just a few possessions, but they tried to preserve some mementos of their homelands. Blankets and tablecloths embroidered in beautiful Latvian or Lithuanian designs cover some of the trunks and suitcases in the opening display.

The exhibit opens with a large map of Central and Eastern Europe at the outset of the Second World War. Near the map is a quote from Timothy Snyder’s book “Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin.” It is frightening to consider how Central and Eastern Europe did indeed become “bloodlands” as a result of the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact of 1939.

The first major portion of the exhibit is called “Flight.” It uses photographs and personal objects to describe the flight of Lithuanians, Latvians and Estonians from their homelands as the Russian Communists pushed westward. The reasons for the flight are sometimes much easier to understand when you consider individual examples. For example, the exhibit contains a dismissal letter for a teacher, Ona Burneikis. Dated February 18, 1941, it specifies that Ona Burneikis is fired because she is found to be unqualified to educate youth in a Communist spirit. Not suprisingly, the Burneikis family was one of the thousands Lithuanian families that fled the second Russian Communist occupation of their country. Later photographs in the exhibit show the Burneikis family after their arrival at the Rebdorf- Eichstatt DP camp.

Some of the photographs demonstrate the primitive conditions under which the refugees fled. We see a photograph of the Gimbutas family fleeing in a horse-drawn cart with suitcases and a baby tram piled on it. One of the persons on the cart is Marija Gimbutas, who later became a famous archeologist, anthropologist, and professor of Indo-European studies at the University of California at Los Angeles. Another photograph shows Latvian refugees making their way through a forest in a caravan of horse-drawn carts.

The “Flight” section contains examples of items that refugees took with them when they left their homelands. Many refugees wanted to take a part of their homeland with them. For example, the Kviklys family took a package of Lithuanian sugar with the Lithuanian words “Gabalinis cukrus” printed on it. The Bakšys family took with them two pieces of Lithuanian soap. And descendants of both families have preserved these mementos, which can be viewed in the exhibit.

The “Flight” section contains examples of items that refugees took with them when they left their homelands. Many refugees wanted to take a part of their homeland with them. For example, the Kviklys family took a package of Lithuanian sugar with the Lithuanian words “Gabalinis cukrus” printed on it. The Bakšys family took with them two pieces of Lithuanian soap. And descendants of both families have preserved these mementos, which can be viewed in the exhibit.

Another map opens the second section of the exhibit, entitled “The Camps.” The map shows the many cities in Germany where refugee camps were located, as well as the division of Western Germany into the British, French and American zones. Photographs document the arrival of Baltic “displaced persons” at the various camps. One photograph shows a room with simple wooden beds. The small room housed four refugee families. However, even under very trying conditions, Baltic “displaced persons” did their best to preserve a sense of order, dignity, and in some cases artistic creativity. The name plate which Vytautas Kašuba, a Lithuanian artist, designed for the six members of his family is a beautiful work of art, which not only lists the names of each family member in elegant caligraphy but also adds patriotic colors and designs to the background.

The exhibit provides a detailed glimpse into the daily life in the DP camps. It is remarkable how the Baltic displaced persons were able to organize their lives, despite the very trying and primitive conditions in which they found themselves. An example of this is an organizational chart which the Lithuanians in Wiesbaden drew up. The chart covers all aspects of life, and resembles a managerial flow chart of a major American corporation. The food situation in the camps is made concrete: the exhibit contains a sheet of food tickets, which the DPs were issued in order to get daily food rations. Photographs show the DPs waiting in line for food, as well as a classroom where the children, with smiles on their faces, receive food items and clothes delivered by CARE packages.

Children find a way to have fun even under the most difficult circumstances. The exhibit shows a photograph of children playing on a makeshift merry-go-round, which appears to have been constructed from railroad beams. In another photograph, Nijolė Lipčius Voketaitis and Emilija Jurevičius dress up their pets in handknitted sweaters. The exhibit also contains a homemade toy rabbit, which Dalia Stakys-Anysas named “Bukutis.”

The reality of camp life for adults, however, was not as cheerful. One photograph shows a well-known Lithuanian professor, Steponas Kolupaila, doing manual labor by carrying a large wooden beam. Another photograph, made by Kazys Daugėla and entitled “Loneliness”, shows a middle-aged woman sitting at a table in a simple room. She is wiping her face with a towel. The title suggests that she is wiping some tears as well.

An important part of the exhibit is entitled “Resistance.” This part of the exhibit shows that the Baltic DPs were well-aware of what was going on in the world around them, and especially in their homelands. We see a photograph of a hunger strike in 1947, which demanded independence for Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. We see a photograph of a DPs protesting Soviet deportations of their countrymen to Siberia. This protest took place in Munich in 1949. But perhaps the most striking photograph is one of an automobile which has been completely torched. The accompanying text explains that a Soviet official had come to the Munich-Freimann DP camp for the purpose of organizing the “repatriation” of DPs to their Sovietoccupied homelands. The DPs reacted to this “repatriation” effort by burning the Soviet official’s automobile and setting alight his “repatriation” propaganda materials.

The part of the exhibit entitled “Maintaining Customs and Traditions” shows that the Baltic DPs carried on a vibrant cultural life in the camps. We see photographs of Estonian folk dancers dressed in traditional folk costumes at the Estonian DP camp in Gottingen. We see a Latvian choral group from Munich as well as the Lithuanian chorus “Dainava” giving a concert in Hanau, Germany, in 1946. Two mannequins tell an interesting story. One is a man dressed in a tuxedo. We learn that this is the tuxedo that Lithuanian tenor Stasys Baras wore at all the concerts he gave in Germany after the war. The other mannequin is a woman dressed in a traditional Latvian folk costume. We learn that the folk costume was made by Rita Treija, a Latvian displaced person in the Esslingen DP camp. She used an army blanket for the skirt. She dyed the blanket and then embroidered it with a traditional Latvian design.

The customs and traditions section includes photographs which show a Lithuanian wedding, a christening in a Latvian family, and the participants of an Estonian-Lutheran confirmation. We learn from the accompanying explanation that the beautiful white dresses the young Estonian girls are wearing were actually made out of parachute cloth. And there is a photograph of a Lithuanian Christmas celebration, which took place in Kempten in 1946 and was complete with a Lithuanian version of Santa Claus. Unfortunately, the exhibit does not give much information about the role of religion in the DP camps. It seems to me that an entire section named “Religion” could have been included.

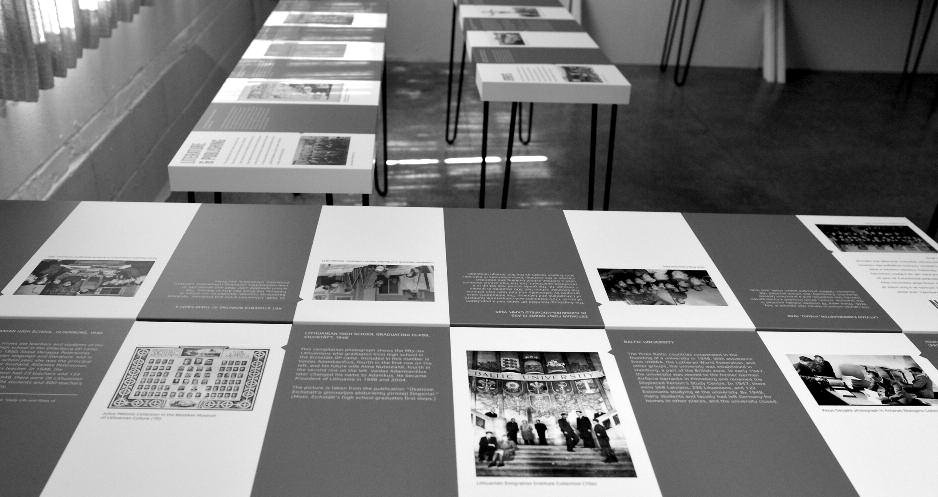

A significant part of the exhibit is devoted to “Literature and Publishing” and to “Education.” The exhibit contains examples of the many books and magazines that Baltic DPs published in Germany after the war. These include a Latvian kindergarten teacher’s handbook, an illustrated Estonian book and a Lithuanian prayerbook “Apsaugok Aukščiausias.” The education section of the exhibit shows that the Baltic DPs organized all levels of education for their children, starting with kindergartens and going all the way to a Baltic University. Some of the accompanying photographs contain very interesting details. For example, the exhibit contains a photograph of the graduating class of the Lithuanian high school in Eichstatt, Germany, in 1946. Among the graduates is a young man identified as Valdas Adamkevičius. He later changed his name to Valdas Adamkus and became President of Lithuania.

The exhibit portrays the efforts Baltic DPs made to prepare for a new life. We see photographs of young women training to become seamstresses, young men learning the craft of brick-laying. One poignant photograph shows two blind Lithuanian DPs in the Neustadt Camp. They are somehow able to work a loom. The Baltic DPs eventually realized that they would not be able to return to their homelands and that they had to prepare themselves for a new life in a new country. For many that new country was the United States of America.

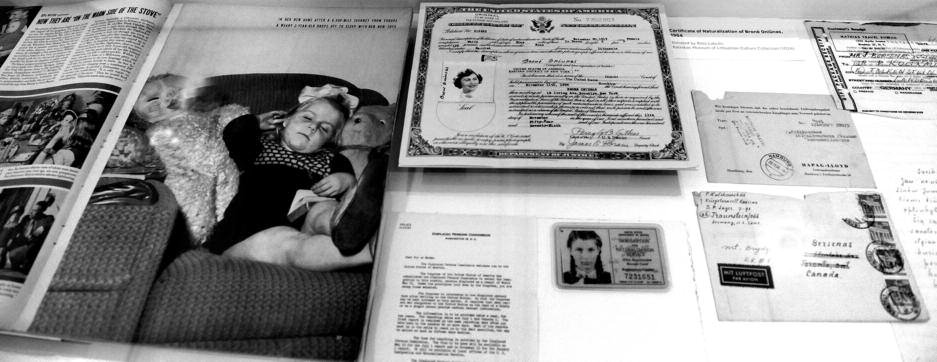

The exhibit gives a very clear picture of how difficult it was to get permission to enter the United States. The required paperwork was staggering. It is revealing to look at all these forms now, when immigration “reform” is so much in the news, and American politicians seem to be scratching their heads to find a way to grant amnesty to illegal aliens without calling it amnesty. The Baltic DPs, in contrast, had to jump through hoops in order to enter the United States legally. There were registration forms, there were forms to prove that you were vaccinated against smallpox, there were required affidavits of support, letters from sponsors etc. Examples of these forms are on display in the exhibit. But for thousands of Baltic DPs, the result was a good one – they got the chance to start a new life in America. It was poignant to see on display an article from Life magazine, dated November 22, 1948. The article described the feelings of new emigrants to the United States with the slogan “Now they are on the warm side of the stove.” It is interesting to read a welcoming letter written in 1949 by Adlai Stevenson, who then was Governor of Illinois. He welcomes the new immigrants to Illinois and says that he prefers to think of them as “delayed pilgrims” rather than “displaced persons.”

The exhibit concludes with photographs of three Baltic presidents. We see a photograph of Vaira Vike-Freiberga, the former President of Latvia. Next to it is a picture of a group of children in the Lubeck DP camp. There is a smiling little girl, Vaira Vike-Freiberga, in the first row. We see a photograph of Toomas Hendrik Ilves, the current President of Estonia, and we learn that his parents were displaced persons who fled Estonia in 1944. And finally we see a photograph of a grey-haired Valdas Adamkus, President of Lithuania, and next to it, a photograph of a young Valdas Adamkus, arriving in the United States in 1949. A fitting close to the exhibit. These three examples show that the Baltic DPs never lost their love for their homelands and were able to rise above adversity and make their mark on history.

For those wishing to have a deeper understanding of the DP experience, read DPs: Europe’s Displaced Persons, 1945-1951 by Mark Wyman (Cornell University Press, 1998).

DRAUGAS NEWS Lithuanian World Wide News in English

DRAUGAS NEWS Lithuanian World Wide News in English