by Stanislovas Žvirgždas.

Balys Buračas (1897-1972) was a photographer who created a vast archive of visual memory of Lithuanian villages and ethnic culture. He was a chronicler, saving the remnants of a life that was fast disappearing from people’s memories. Many post-war Lithuanian art photographers have long acknowledged that they grew up and matured within the traditions of ethnographic photography pioneered by him. How did the creative journey of our distinguished photographer begin?

In his autobiography, Balys describes the beginnings of his interest in photography at the age of 18: “I obtained my first camera on April 14, 1915, and it was then that I learned how to take pictures.” Balys Buračas got this camera from a German soldier whose unit was marching through the town of Šiaulėnai, near Buračas’ birthplace in the village of Sidariai. For the camera, Buračas had exchanged a wooden staff containing artistic carvings of snakes, leaves, flowers and birds. It was a metal camera with bellows, equipped with 6 x 9 cm. glass plates to hold the negative. The shutter had only one exposure speed of 1/2 second, and the very simple lens did not have an adjustable aperture. Buračas quickly obtained some materials for developing photographic film, and then boldly began to develop his first photographic plates. In his initial attempts, he was able to print out a fairly good picture from the wet negative, but then the emulsion dripped away when he tried to use fire to dry it. Later on he had better luck. The 18-year-old photographer learnedhow to take photographs in the region of Šiauliai. “I began with familiar locations where I had seen cottages and barns decorated with wood carvings as well as other examples of the art of woodcarving.” Having once tried photography, he got caught up in it, and it became his life’s passion.

In 1919, Buračas joined the Lithuanian army, but was released when he fell ill with tuberculosis. The next year, he completed his studies at a teachers’ college in Šiauliai, and for the next seven years he supported himself as a teacher and administrator in various schools in the region.

In 1924 the painter Adomas Varnas was concerned that wayside crosses, which in his opinion were national artistic treasures, were fast disappearing. Varnas engaged Buračas to help him preserve this legacy art form. As Varnas wrote to the young ethnographer: “Maybe it would be worthwhile to take up this work seriously. We should do this work not for profit, but in order to rescue treasures which are in danger of perishing.” Buračas began to systematically photograph these crosses, sending the pictures and negatives to Varnas. Once, one of Buračas’ photographic journeys turned into an adventure. He stopped at a cemetery in the town of Šaukėnai to take pictures of some gravesite crosses. As he was quietly engaged in his task, a group of local women gathered and began to shout at him: “You atheist! Get out of the cemetery! The pastor said that you left your bicycle by the house of Mykoliukas, a scoundrel just like you. How dare you knock down our crosses?” It made no difference to the women that he had come not to destroy but to preserve the memory of these intricate crosses carved by gifted artisans. Balys had to jump a fence to avoid pursuit by the angry locals, otherwise his camera might have been smashed.

In 1928 Balys Buračas gave up his job as a teacher and devoted his life to photography and ethnography. In an orderly fashion he compiled books of photographs that catalogued folk art and village people at work and attending various social events. The notes of Balys Buračas give us an idea of the scope of his ethnographic efforts. “… In 1929 I traveled across Lithuania at the request of the M. K. Čiurlionis Gallery, and I collected examples of folk art. I took about 300 photographs of 10 x 15 cm.; … In 1932 I took about 700 negatives in eastern, northern and western Lithuania [“Rytų Aukštaitijoje, Šiaurės Lietuvoje ir Žemaitijoje”]; … In 1933 – 700 photographs in southern Lithuania [“Dzūkijoje”]; … in 1934 I took about 800 photographs, and I took notes of the folklore and folk customs in the region around the villages of Kupiškis, Skapiškis and Šimonys; … In 1936 the Museum of Vytautas the Great in Kaunas sent me to eastern Lithuania [“po Rytų Aukštaitiją”] where I took about 300 photographs.” There washardly a magazine or newspaper in pre-war Lithuania that did not have photographs of Balys Buračas or did not contain his articles about folk customs, festivals and traditions. In 1937 Balys Buračas won a Great Gold Medal at the Paris World Fair for a collection of 25 ethnographic photographs. After he won the gold medal, his photographs were published in journals of other countries. They appeared in Illustrated London News, in the French encyclopedia Larousse, in the Czech and German press, and in the press of Lithuanians living in the United States.

In his genre photographs Buračas succeeded in capturing an instant of time, as if he had inadvertently come upon people busy at their daily labors, selling goods at market, celebrating weddings, grieving at funerals, going to church or putting up crosses by their homes, in cemeteries or by village roads. He photographed folk artists, women at the spinning wheel, carpenters, young shepherds in the fields, participants in village fairs, singers, storytellers and matchmakers. Often he would wait until the subject had immersed himself in his or her work and had forgotten that there was a photographer present watching him. Buračas meticulously recorded when and where each photograph was taken, and what it depicted. He liked to give precise descriptions of the objects or customs portrayed in his photographs, and he added colorful biographical details to his photographs of folk artists. These photographs and their accompanying notes provide us with a chronicle of past Lithuanian life. They are a visual record of the memory of Lithuania which cannot be duplicated. The old spirit of the nation lives on in the moments captured in his photographs.

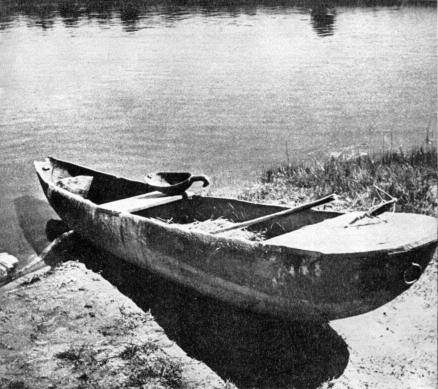

By the spring of 1944 Buračas had amassed an archive of about 18,000 negatives and 26,400 prints. He had walked or ridden across all of Lithuania, visiting even the smallest population centers. “There is no city, town or village that I did not visit.” Unfortunately, a large part of this archive perished during the Second World War. Even during the years of the war when Lithuania was under German occupation, Buračas continued to travel across Lithuania, and he provided the press with his descriptions of Lithuanian customs illustrated with his own photographs. The photographs of Balys Buračas filled all of the publications permitted at that time, including the magazines Į Laisvę (Into Freedom), Ateitis (The Future) , Naujoji sodyba (The New Homestead) and Žiburėlis (The Light). After the Second World War, Buračas continued to take pictures, and as a certified photographer he traveled along river banks and photographed burial mounds, historical sites and cultural monuments.

In 1953, Buračas nominally retired, but he continued taking pictures because he felt he had to preserve quickly what war and time had not destroyed. He again traveled to villages, and he was able to find prewar ethnographic motifs and to repopulate with new photographs archives which had been destroyedin the war. He added 2,500 negatives to his collection during the years 1957 to 1960, when he again visited all of the principal regions of Lithuania. In 1965, as Balys Buračas celebrated his 50-year anniversary of ethnographic work, he wrote: “Get the idea out of your head that after you cross the half-century mark, the days of your life are declining, or that your steps are becoming shorter and slower. Just think about how little you have done and about how much more you can do, because no one else is going to do it.”

Balys Buračas was one of the foundational pillars on which the school of Lithuanian photography was built and continues to rely. His impact was to show how documentary and artistic photography could be organically fused. Comparatively little was written about him while he was alive. Just before his death, in 1971, Virgilijus Juodakis authored a short book entitled Balys Buračas (Vaga Press). In Lithuania, Buračas’ work was increasingly recognized in books of photography published after his death, in 1988, 1999, 2006 and 2011. In 2000, an exhibition dedicated to his work, titled “Photographs from Central Europe I” was held in Berlin. Art critics describing the exhibition emphasized how the spirit of pre-war Lithuania was illuminated in these photographs that showed people who were full of vitality, energy, hope and belief in the future of a young and modern country.

We should be proud that Lithuania had such a classic photographer. He is someone who can easily be included in the world history of photography. If Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis gave us a soul, Balys Buračas gave our country a body. Today a large photographic archive of Buračas’ work can be found in the Vytautas the Great War Museum in Kaunas (more than 11,000 negatives). The National M. K. Čiurlionis Art Museum has over a thousand photographs, and other museums number his photographs in the tens and the hundreds.

Translated by Rimas Černius.

DRAUGAS NEWS Lithuanian World Wide News in English

DRAUGAS NEWS Lithuanian World Wide News in English