Personal Memories of World War II, Lithuania, and the Lithuanian Diaspora

By VALENTINAS RAUGAS.

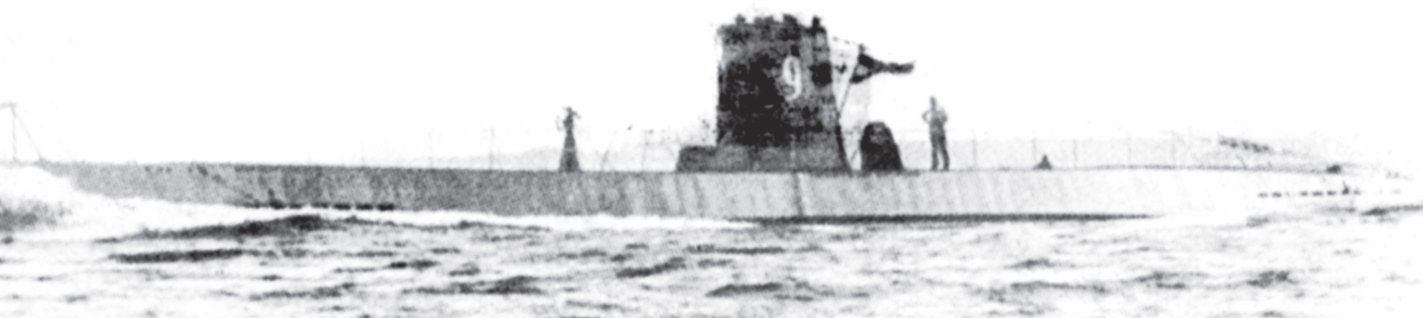

As a recreational New Jersey wreck diver for ten years, I had the opportunity to do two separate dives on german u-Boat 853. This wreck was a german electric submarine which was sunk on the East Coast off rhode Island during world war II. It rests at the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean at 130′ feet in depth. Its location is 7 miles off Point Judith and near Block Island.

U-853 is one of the most popular wrecks on the East Coast and is heavily dived by East Coast divers. It is an exciting but also a dangerous dive. For penetration divers that enter the wreck, the tight spaces in the submarine, sharp metal edges, and debris all pose hazards. As of 1993, at least three divers have died on this wreck. One of the divers lost was killed by an explosion. On Nautical Charts, the dive site location of U-853 is marked with the warning: “Danger, unexploded depth charge, May 1945.” Immediately after its sinking Navy Divers attempted to enter the wreck but failed to do so after two days of diving. (Wikipedia)

The dive on U-853 is one of the most exciting and most remarkable of my diving experiences. Not only from the perspective of sport diving but also because it was a relic of a time and place which had a profound effect on my life, as well as millions of others. Namely: World War II.

This experience was relevant on two levels: the actual dive itself and the precipitation of a number of memories related to my own life-experiences during and after World War II. This added another dimension to the dive.

This dive had a personal meaning beyond just being a deep dive in the Atlantic. Anticipating the dive, I knew that I would be encountering a relic of the past: namely a close encounter with an ominous and deadly member of the German war machine. The idea of such an encounter brought back many memories, both before, after, and during the actual dive.

Memories of World War II: Lithuania and Germany

I have memories of seeing German soldiers aboard flat boxcars on trains passing through Vilnius, Lithuania in great numbers. Most likely to and from the Eastern Front. They frequently threw candy to the children just like Americans did later in Germany.

I also have vivid recollections of air raids both in Lithuania and Germany during the war. The loud wail of the sirens which relayed the message of imminent danger. The accustomed routine of turning out the lights and “going dark,” and then descending to a basement or an air-raid shelter.

On one occasion in Germany, an Allies’ plane was shot down nearby and people had gone to the wreck which lay in the farm field within walking distance. One man came back with a pair of binoculars and was showing it to others. I had very little awareness of the nationality of these airplanes, being only four or five years of age. In Lithuania, they could have been both German and Russian at different stages of the war. In Germany they were most likely American or British until the end of the war. The occupation forces were French in the area of Germany where we were living and working on a farm for our shelter and keep.

One of the most poignant memories in Lithuania was that of a woman trying to flee or escape in Vilnius during the German occupation when I must have been three or four years of age. As she was desperately trying to run, a German officer confronted her with a drawn pistol and shouted for her to stop. This occurred only several feet from where I was with my mother, who grabbed me by the arm and quickly walked away from the scene. I was told that the fleeing woman was Jewish. This had a lasting impression on me and the memory remained vivid throughout my life.

There also was an active underground and resistance movement both during the German and the Soviet occupations. During the first Soviet occupation the Russian army and the NKVD rounded up thousands of Lithuanians who were deemed to be “enemies of the state” and shipped them off to Siberia. Massive deportations were to follow after the Soviets returned and occupied the Baltic States in 1944.

During the last days of the war, I clearly recall being in a field and seeing German soldiers fleeing as the French forces advanced into our area. The French were deployed in tactical infantry formation and consisted of Moroccan soldiers. I had never seen a black person prior to this.

Later, with several of my friends, I found an abandoned shack in the forest which had a cache of Nazi weapons and Nazi posters on the walls. We reported our find which was turned over to the French military authorities. Later, during a Boy Scout trip we found and played in destroyed buildings and abandoned steel wreckage. We found live ammunition there as well.

When fleeing Lithuania by train there were shots fired at our train as it traveled en route to Germany. The shots might have been from a machine gun position located in a forest. I also learned much later in life from my parents that their goal was to reach the Swiss border. They were turned away at the border because they would have to pay a large sum of money in order to cross into Switzerland. I was unaware of these plans until shortly before my parents died. Subsequently, when I skied in Switzerland on two occasions a couple of years ago, I did think of what the eventual outcomes would have been had they crossed the border and remained in Switzerland.

They did wind up working as farm laborers in southern Germany for the duration of the war. There also were Russian prisoners being held there but they were kept separately. On one occasion, some Lithuanians in the group, and probably my mother as well, gave the prisoners some food. This was forbidden and German officers arrived the following day on an official visit to issue a warning. Near the end of the conversation, one of the officers warned my parents that if this should happen again they would find themselves in a German prison. The officer then made a gesture to reinforce his point. He extending two fingers from each hand and then crossed them, depicting a jail window. That was the warning.

In my entire life I never saw this gesture again, anywhere. I have to assume that this may have been idiosyncratic to German military, being that they were mass jailing or sending millions to concentration camps. Given the gesture, one might say “at the flick of four fingers” one can wind-up in a jail cell or concentration camp. No court, no lawyers, no civil rights. Those that carried the guns had the last word. Power over life or death at the flick of a wrist or pointing of a finger. The Russians usually came at night and people just disappeared. Talk about intimidation!

The Lithuanians referred to concentration camps as “Acetates.” If you were sent to the Gulag by the Russians, then you went to “Sibiras.” “Gulag” only came into usage after Solzhenitsyn. My father, a former Lithuanian Army officer, would have been jailed or sent to Siberia when the Soviet Army reoccupied Lithuania in 1944. The German gesture certainly must have made a lasting impression on him. He later learned that the NKVD, the forerunner of the KGB, interrogated and tortured my grandfather, trying to find the whereabouts of his son, my father.

I also remember now when the Lithuanians sailed in small sailboats from Klaipėda, Lithuania, to New York City Seaport in the early 1990’s in a celebration and display of “Sail for Lithuania’s Independence.” The first sailor I encountered as he stepped from a small sailboat was a sailor by the name of Jonas Dovidėnas. As he stepped from his sailboat, I shook his hand, took a photo and told him that it would be the Lithuanian Karys (The Warrior) magazine’s next edition. He looked at me and said, “I know Karys— my father was a Lithuanian army officer and I spent nine years in Siberia (Gulag).” I looked at him stunned and in amazement. I quickly realized that this could have been me. Later, when I gave the photo to my father, who was the editor of Karys in exile, I asked him to be sure to give the photo a prominent place in the magazine After all, the guy did nine years in the Gulag. First guy off the boat and nine years in Siberia. As I usually say at military funerals for those currently “Killed in Action” — “It is an honor.”

Another frightening experience was before the war ended. A Hitler Youth group (Hitlerjungen) were rumored to be coming to our area for a jamboree. They had a reputation of being very aggressive and nasty. When they arrived, we stayed far away from their camp. One day we did sneak up to their campsite and observed them from a safe distance as they went about their business. I was more frightened then than I was during the German officers’ visit at the farm.

I also remember being called Auslander (“Foreigner”) by the Germans. This occurred frequently and was said with derision. Later, living in a tough South Philadelphia neighborhood some kids would call you “DP,” short for Displaced Person. This wasn’t so bad since it motivated one to learn to speak English real fast and also had another prerequisite: to learn how to fight. The latter being more important than the English.

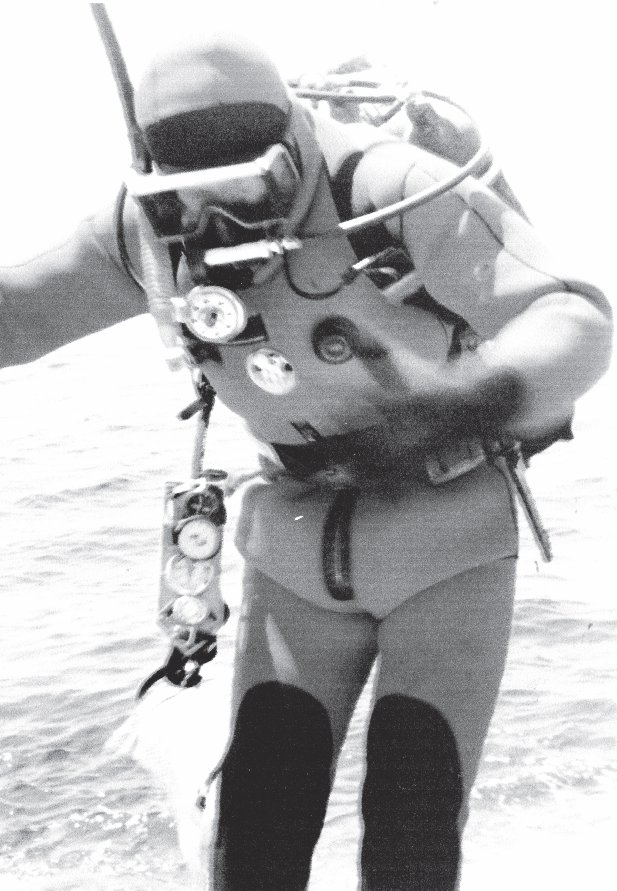

Diving U-853

As one descended using the anchor line, with decent visibility one could see the wreck from a long distance lying on the ocean floor. As one came closer, the features of the wreck became clearer. The wreck was relatively intact and not just a bunch of blown-up metal scattered on the ocean floor. It was a sleek German submarine sitting upright at the bottom. The conning tower made the sub look ever more imposing. I forgot to look to see if there was a swastika on the conning tower.

This was a close encounter with a German submarine that was only seven miles off the East Coast: deadly, ominous, and stealthy. Although my memories were many, I had to concentrate on the dive: not to exceed the bottom time, monitor the air, and stay focused. I also had to have awareness of my location on the sub in order to find my way back to the anchor-line in order to have a controlled ascent to the surface.

Once back and safe on the boat, I allowed my thoughts to take me back to some experiences of living in Germany during and after World War II. The submarine base and training facilities were in Bremen, a major German port. When my family, as Displaced Persons, left Germany for America in 1950, we sailed out of Bremen. As I recall, Bremen was still in rubble in 1950 more that five years after the British bombing. Was the submarine fleet one of the major targets?

Was U-854 there at the time when we sailed out of the harbor? Had it been there, in my wildest dreams I would not have thought that I would lay my hand on its hull at the bottom of the Atlantic and near the coast of America.

I did not dwell too much in my thoughts on the German submarine crew lost on the boat. They were called Kreigsmarine and were one of the most elite and admired military units in the German military. Their casualty rate towards the end of the war was said to be at about 75 percent. As a result, the U-Boats were called “Iron Coffins.” When they sailed from their ports, most sailors did not expect to return.

Military ships sunk during the war were designated as national cemeteries. In 1990 a diver brought up a skeleton from this sub. The German government reacted with outrage and the skeleton was buried with military honors in Newport, marked by a gravestone that read in German: “An unknown German seaman from U-853.” (from uboat.net)

Prior to its sinking, U-Boat 853 attacked and sank a U.S. freighter, Black Point. This was on May 5, 1945. It was chased later by the U.S. Navy destroyers and was sunk the following day by a direct hit from a depth charge less than four miles from Point Judith, R.I. The ship is 368 feet in length but the stern was blown off during the attack. Otherwise, it lies intact in 100 feet of water. Twelve of the crew died and 34 were rescued. (from uboat.net)

Each time we dove the U-853 we did our second dive on Black Point. This increased the significance of the dives, since we were diving both the attacking enemy submarine and also its American victim ship. What is also fascinating is that the German submarine was very close to the U.S. Coast. Also, my diving partner found a large human bone outside of the wreck on the ocean floor. Both of the ships are designated as official tombs by their respective governments. The protocol when diving is to treat it as you would a tomb in a cemetery. The ships serve as self-enclosed tombs or “Iron Coffins.”

There were other German submarines scattered along the entire Atlantic Coast of the U.S. U-Boat 879 was off the coast of North Carolina, in the vicinity of Cape Hateris, and was also frequently dived. U-Boat 879, was in the vicinity of Boston.

One of the finest books on submarine warfare is “Operation Drumbeat: The Dramatic True Story Of Germany’s First U-Boat Attacks Along The American Coast in World War II,”written by Michael Gannon.

Operation Drumbeat was the submarine campaign which was launched by Hitler and Donitz against the U.S. In 1942. The objective of this plan was to sink and destroy the American convoys of freighters in the Atlantic that were delivering war material and supplies to the British. Successful implementation of this plan would result in Germany winning the war. During the first six months of implementation, the German submarines sank close to 400 American ships off the East Coast, Gulf of Mexico, and the Caribbean, while losing only six U-Boats.

The strike by the German U-boat submarines on the East Coast of the United States was planned to have had the same effect as the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor had on the West Coast and the Pacific.

U-Boat 869

There were rumors in the diving community in New Jersey that there possibly was a submarine off the New Jersey shore. Finally in 1991 a German submarine was discovered 50 miles off the coast in the vicinity of Point Pleasant, NJ in 230 feet of water. This discovery was highly unusual.

It was located by two New Jersey weekend wreck divers, John Chatterton and Richie Kohler. Their story is told in the book “Shadow Divers: The True Adventure of Two Americans Who Risked Everything to Solve One of the Lost Mysteries of World War II” written by Robert Kurston, journalist and author out of Chicago.

The book became a top best-seller in 2004 and is one of the best diving books ever. Jacques Cousteau could not have done a better job. At the time of the publication of the book, three wreck divers had lost their lives on this deep wreck. The diving was extremely dangerous, being 100 feet above the recommended limit of 130′ for sport divers. Special mixed gases were used by the divers and they had to work in the dark or “in shadows.” The penetration of the wreck by Chatterton, in order to find its identification, is beyond description in terms of danger and excitement to read.

Eventually, after extensive research, which included several trips to Germany, the wreck was identified as U-Boat 869. Official German government records had no listing of that particular submarine being in the vicinity of the North American coast. Its records had its location in the vicinity of Gibraltar. It was also an electric submarine of the same class and identical to UBoat 853 in Rhode Island dived by this author.

After the unknown sub was identified as U-869, Chatterton and Kholer did some follow-up and made personal contacts with several relatives from the submarine crew. U-869 had gone down with a crew of nearly 50.

Otto Brizius was the youngest of the crew at age 17. He had a German first name but was certainly of Lithuanian descent on the father’s side. His half-sister was located living in Maryland and within 150 miles, plus 50 nautical miles, from the location of U-869. She was also said to be fluent in German. She was flabbergasted that she was living so close to the “Iron Coffin” of her brother. For her entire life she had thought that he was missing somewhere in the Atlantic near Gibraltar.

Otto Brizius joined the submarine service wanting to be part of the elite and glorified German submarine branch. There is extensive biographical data on Google which was written by his half-sister. However, there is no other explanation as to the Lithuanian last name.

Nevertheless, he was part of a deadly German submarine force which was at a pivotal point in the future of the war. His submarine was there to sink and kill Americans, such as the crewman of Black Point whose leg bone was held in the hand of my dive partner.

“These were kids that gave their lives for their country as we gave ours. This is the result of war. It’s a grave.” This was reported to be said by Bill Palmer who is probably one with the most experience on diving the U-853. He was the dive boat captain on both of my diving excursions on U-853.

It is of further irony and tragic that on the day of the sinking of Black Point, Karl Donitz, President of Nazi Germany ordered all U-Boats to cease offensive operations and a return to their bases. UBoat 853 never received this message. It could have been a non-delivery error in German communications or radio failure on the sub itself. Whatever the cause, 12 American Merchant Marine sailors died on that day. The next day 55 German sailors perished in U-853, on the day before Nazi Germany surrendered.

Author’s Note:

“Hitler’s Lost Submarine,” a documentary done by PBS was shown on national TV on NOVA. it pretty much followed “Shadow Divers” with additional information provided on the German and American submarine warfare and the taåctics involved. it is one of the best documentaries ever done on the subject. it can be seen on the Web.

“Das Boot,” a German award winning film, continues to be rated as the best film on the topic of German submarine warfare. it certainly defines and captures the essence of “iron Coffins” where the casualty rate of German submariners was said to be at about 75%. in combat, a casualty rate of 30% (KiA-Killed in Action) is considered to be exceedingly high.

DRAUGAS NEWS Lithuanian World Wide News in English

DRAUGAS NEWS Lithuanian World Wide News in English