Interview (1988) by George Hodak.

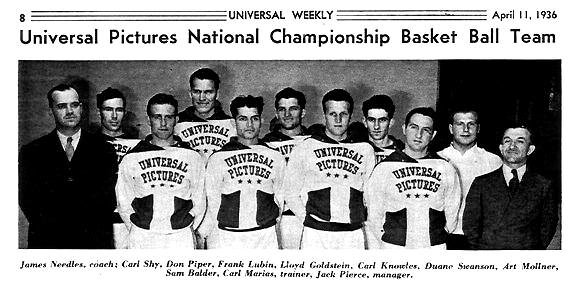

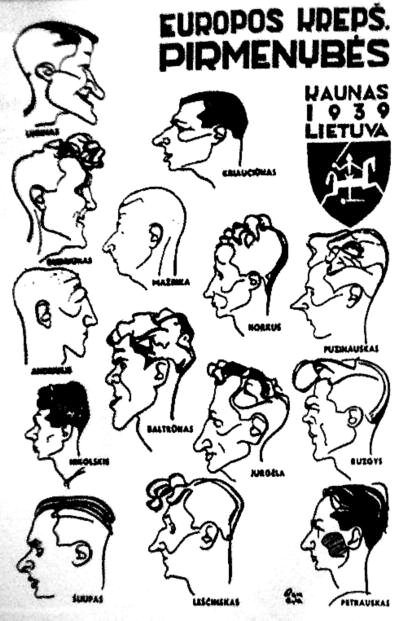

75 years ago, Lithuania hosted the European Basketball championships in Kaunas and won. Part of this success can be attributed to Frank Lubin (Pranas Lubinas), one of the greatest basketball players the us produced in the days before professional basketball. he started his big-time career with UCLA, graduating in 1931, and then went on to star in amateur athletic union (aau) competition for over 30 years. he was on the universal Pictures team which contributed seven players to the 1936 Olympic team, and also played with the 20th Century Fox team. in 1936 and in 1939 he coached the Lithuanian national basketball team and led it to the European Basketball Championship. Frank Lubin died in glendale, California on July 8, 1999. this interview was part of an oral history project conducted by the amateur athletic Foundation of Los angeles in 1988. George A. Hodak talked with Frank Lubin about his life and his love of basketball. here are a few excerpts, which hopefully will be of interest to Lithuanian americans and to all basketball enthusiasts.

THE EARLY DAYS

Hodak: First off, I’d like you to talk a bit about your family background.

Lubin: I was born in the east side of Los Angeles, in the Belvedere area, on January 7, 1910. I came from a family of four boys and two girls. My father and my mother came from Lithuania. They were forced out of Lithuania by Russia, which occupied their country. My father, a tailor, provided a good living for a family of seven.

Tell me what sort of things you were interested in as a youngster?

My first interest in sports was in high school where I tried out for the track team, the baseball team and the football team. Finally, as I was growing fast at this period o f my life—I grew from about 6 feet to about 6-foot-5—one of the players on the basketball team asked me to come out for basketball because they needed a big center. In 1927, without any help from my family or anything, I graduated from high school and went to UCLA.

When you decided to attend UCLA, did you have it in mind to play on the basketball team, or did someone approach you about it?

I was never approached. I tried out for everything. I tried out for baseball, football, track, and I even went out for the swimming team. I knew how to swim quite well and thought I was going to be a great swimmer at one time. The coach of the Olympic team saw me swimming at the Hollywood Athletic Club, where the UCLA basketball team practiced, and he said he wanted me to go out for the swimming team. He was going to make me an Olympic champion in the backstroke. But I was taking to basketball about that time. In 1931 I was picked on the second All-Coast basketball team.

Following your graduation from UCLA, what were your intentions?

My family thought that I should become a lawyer because that was a good profession and it paid well. To get a good paying job was uppermost in most people’s mind. So after graduation from UCLA in 1931, I went to the University of California at Berkeley for law school. But basketball was in my blood, so before law school, right after graduation, I started playing basketball for a local team called the Pasadena Majors, which went to the national AAU tournament held in Kansas City.

While you were attending law school at Berkeley were you also competing for the Olympic Club in San Francisco?

At the time, another athlete that played at UCLA, Carl Knowles, had moved to San Francisco. His family was running an oil station there. Carl contacted me up at Boalt Hall and said he was playing for the Olympic Club in San Francisco and that they needed a big center. He asked if I would have time to come out and play basketball. I said, “Oh gee, that’s my second love.” So I said I would come over and play for them. We had a strong team and won the Northern California championship in basketball and were invited to go to Kansas City again.

Take us from your days in school at Boalt Hall and competing with the Olympic Club to your move south back to Los Angeles.

Well, in 1933 I wasn’t doing too well in school.My grades were suffering from my playing so much basketball. Although I worked in a law firm and was making 50 dollars a month, it wasn’t enough to keep me in school. Things were kind of rough in the years 1929 to 1932; my dad lost his tailoring business, so I came back home. While looking for a job I was contacted by a gentleman from Universal Pictures. Jack Pierce was the makeup man at the studio. He asked me to come out for the team at Universal Pictures, which I did. And he got me a job there which helped with my family affairs. I continued working there for three or four years.

Well, let’s talk a bit more about the Universal Pictures team and Jack Pierce in particular.

Jack Pierce loved basketball, though he never played. He was a smallish man and a makeup artist at Universal Studios. And he’d invite players to come to the studio and he’d get them jobs in the business; some of them in the laboring, some in the camera department and elsewhere. The Universal Pictures team was playing and traveling around a bit to the Midwest—to Denver, Kansas City and Tulsa. Jack was a makeup man on the Bride of Frankenstein. So he asked me if he could make me up as Frankenstein when we made this tour to publicize the Bride of Frankenstein. I said, “Oh, sure, of course.” So he brought along the makeup to put on my face and my hands, the six inch high raised shoes, the ragged coat, a headdress and the little metal bolts to put on my neck. And I really looked like Frankenstein.

And you would come out before the games?

(Laughter) I’d come out before the games and stimulate the crowd, walk in front of them and they’d get excited. I wouldn’t play in that uniform; I’d go back to the dressing room after five or ten minutes and our team is already playing, maybe losing, and I’d come back out in my regular uniform and start playing in the game.

I imagine the sportswriters started to call you Frankenstein.

I became known as Frankenstein all around the Midwest and I don’t know how far east. But I was “Frankenstein Lubin,” that’s where I got my nickname.

At what point did you become a more refined center? When did you start to learn the nuances of playing the pivot?

crowds before games. Pictured here with Jack Pierce.

In 1934, Universal Studios had a player that I considered the greatest in the United States at that time, Charlie Hyatt. He had played for Pittsburgh University. He was the all-round player that I always admired. He was 6-foot-1 or so, and he wasn’t the center type, but he was a very fast player, a good defensive man, and the leader of the team. He told me, “Lubin, you’ve got to play center for us. You’ve got to get up on the front line there. I’ve got a man who will teach you to play the pivot position.” So he brought out a man he knew from Chicago that had taught basketball for some time. He taught me how to go right and left and shoot the one-handed shots under the basket. That’s where I remained from then on.

You would play with your back to the basket and try to get the ball near the basket?

Absolutely. In those days, there was no three-second time limit in the key slot and you could back your defensive man right under the basket. I’d have him on my back and I’d have my teammates pass in to me, and they learned that I could shoot either left- or right-handed. And I had a quick step at the beginning to get away from the defensive man. So I started scoring very prominently.

And you would get a lot of rebounds too?

Naturally. I’m 6-foot-6-and-a-half and I could rebound with the best of the basketball players at that time. Not too many of them were that tall.

Would you say you jumped pretty well?

Well, they didn’t allow dunking at that time but I got up near the basket. I mainly banked my shots in; I wouldn’t try to dunk them. So I was safe on that score, where a lot of players trying to dunk would be called for having touched the ball over the rim of the basket. I’d like to say that about that time the rule changes started to come into play. The first one was the center jump. Some of the centers were so tall, and then some of the other teams did not have a tall center; so the taller team would have the tip every time. The better team would get the ball, score the basket, and go to the center to get the center tip. Then they’d get the ball again and go score again. So the scores would be in favor of the taller team. About that time different coaches asked the rules committee to put in a new ruling. The rule came in that after a basket the team that was scored upon would get the ball out of bounds under their own basket. This would neutralize the big centers.

So this is a rule that was in effect by the ‘30s?

That’s right.

The team at Universal Pictures would play AAU teams in the Southern California area and elsewhere. Would you also play colleges?

In those days there was no ruling that said you couldn’t play against college teams. We played against UCLA and USC with the Universal Pictures team. In that era, the pros were not in effect yet. No one was playing pro basketball except back in the East — The Globetrotters, the Celtics and the German Spas from Philadelphia were the only pro teams; they would travel around the country showing off basketball skills. But here in Southern California, and I think all over the United States, organizations, clubs, as well as Hollywood studios were organizing basketball teams for publicity purposes, and perhaps write-offs. They’d sponsor teams and get these boys jobs. Universal Pictures would play against Twentieth Century Fox, MGM, RKO … But other organizations also came in. There was a cafeteria that sponsored a team. Bank of America sponsored a team, and an aircraft plant sponsored a team.

ONTO THE 1936 OLYMPIC GAMES

Carry us up towards the 1936 Olympics. [Ed note: Basketball became an official part of the Olympic Games in 1936.] Had you even heard much about the Olympics and the possibility of basketball being included in Olympic competition?

Actually, I think the athletes didn’t even think about the Olympics. We didn’t feel that we were Olympic material. Our Universal Pictures team played well in Southern California and we won the right to go to Denver. Jack Pierce was involved with his Bride of Frankenstein movie and he couldn’t go. One of the sportswriters here in California recommended a coach to Jack Pierce, “This man just came from San Francisco, Jimmy Needles, a wellknown coach in Northern California. He could possibly help your team.” Since this was an Olympic year we thought he might help us get somewhere on the road to the Olympic competition. The Olympic Committee decided to select one organized team to be the Olympic team and represent the United States in Berlin, Germany. They selected the five collegiate champions in the various areas of the United States, the top YMCA team, and the top two AAU teams, which included the McPherson Globe Oilers and Universal Pictures. We all met in New York, and in the finals the McPherson Globe Oilers had to meet the Universal Pictures team. In the final game, Universal Pictures defeated the Oilers by a score of 44- 43, and won the right to represent the United States in the Olympic Games in 1936.

So as a result of this final game, you and the other members of your Universal Pictures team were on the Olympic team. But there also was a number of selected members of some of the other teams in the tryouts who were chosen to make up the Olympic basketball team.

Well, in the Olympic rule book you were allowed 14 players on a team. However, when we got to Berlin they said only seven could play. So, in the beginning they selected our seven men that played throughout the tournament in New York; six of the McPherson Globe Oilers; and one from the third-place team, the University of Washington, Ralph Bishop. 14 of us were on the Olympic team. Our manager, Jack Pierce, received a telegram saying the team should be in New York by July 12, the boat sails the 13th. But we did not have a sponsor —Universal Pictures took their name off our backs and said they could not sponsor us to go to Nazi Germany. So we were in a bad way.

How were you able to get back to New York then?

We were stuck here in Los Angeles and Braven Dyer, Sr., who was sports editor of the Los Angeles Times, said that he would organize a team to play our team in the Olympic Auditorium to raise a sum of money to get us on our way—which he did. We played an all-star team here and, incidentally, the team, which was made up of a lot of very good college players from USC, UCLA and Loyola, beat us, 22-20! (laughter) And people were saying that perhaps they should send that team to the Olympic Games, that we weren’t strong enough.

And in addition to this game you had to also play a number of other exhibition games before getting to New York.

Yes. Somehow someone organized it so that we’d play in Denver, Tulsa, and Kansas City, until we got enough money to get to New York. As a matter of fact, I telegraphed my wife, my dad, and my wife’s sister, who were in New York, and I said: “Don’t get on the boat to go to Berlin until you see us there.” (laughter) Because we were still playing and paying our own way to get to New York. This was a great disappointment to us; the Olympic Committee at that time did not have the financing that it has today.

Once you arrived in Berlin did you find the Olympic Village in Berlin pretty impressive?

The Berlin Olympic Village was really impressive. The Germans built living quarters for the athletes out of stucco; they had visions of using it as a military encampment later on—which we understand they did. We had wonderful facilities there. But, our basketball facilities were nil. They did not build an indoor gym. Hitler apparently didn’t have a team and he didn’t see fit to build a big basketball pavilion to house basketball because it wasn’t important to them at that time. So we had to go out and practice on a dirt court. We played the games outdoors in rough gravel and the dust would get on our hands. It was very uncomfortable playing in this situation. But we waltzed through all the teams until we played the final game against Canada. It rained that day—and in the second half it poured! There were two inches of water on the court. If I could show a picture of that you’d see a wall around the court and the water just laying all over the court. There was absolutely no dribbling; it was just passing. You couldn’t dribble, it would just splash in the water. I think the only people in the stands were our friends and wives and husbands of the officials. We finally won, 19-8.

Are there other things that you saw in Berlin that stand out? Did you find the Games particularly well organized?

Well, as far as basketball is concerned, we found the facilities atrocious. Playing on the dirt is just like playing behind the church in Belvedere where I first started playing basketball. And then playing outdoors in the rain was horrible. Otherwise the Olympics were beautifully organized. There was a lot of camaraderie amongst the athletes in the Village. In the 1984 Olympics you saw a lot of pin trading. Well, in 1936 they didn’t have pins but people started trading their uniforms. I don’t think I got one piece of my uniform back. I met Japanese and Afghanistanis . . . . I got an Afghanistan sweat outfit. I traded mine with them. We traded our hats, our playing outfits, and our shoes… There was just a wonderful friendship among all the athletes. Of course, we saw the Nazi flags all over the city and we saw the German soldiers. There were young kids who were our guides. They were young 10-, 12-, 14- year-old kids who would guide us around the city whenever we wanted a guide. They were dressed in little white uniforms. We had passes on the buses and we could go anywhere in the city. We ate at the Village anytime we wanted. We’d just go to our restaurant and eat. All this seemed so beautiful until after the Games. I stayed there a week after the Games to make arrangements to go to Lithuania with an athlete that came down from the educational department in Lithuania. He asked my dad, my sister-inlaw, my wife and me if we wanted to see the city. We traveled around on a bus until we saw a nice restaurant. Then we said, “Let’s go in there, it looks very nice.” And he said, “Oh no, we must not go there. Do you see that Star of David there? It’s their restaurant. If we go there we’ll show sympathy to the Jews and it might prove harmful to us.” So we said, “Alright, we’ll find a different restaurant.” Then he asked, “Do you like swimming?” So we went to a swimming hall and in the doorway there was a big sign that said: Juden Verboten. We asked him what that meant, and he said, “That means that Jews are forbidden.” I said, “These signs weren’t here before.” He said, “No, since the Olympic Games are over all the signs have been returned to these establishments.” So I saw a harbinger of things to come. It made us feel very glad to get out of Germany and get up into Lithuania, where it was a friendly nation.

IN LITHUANIA

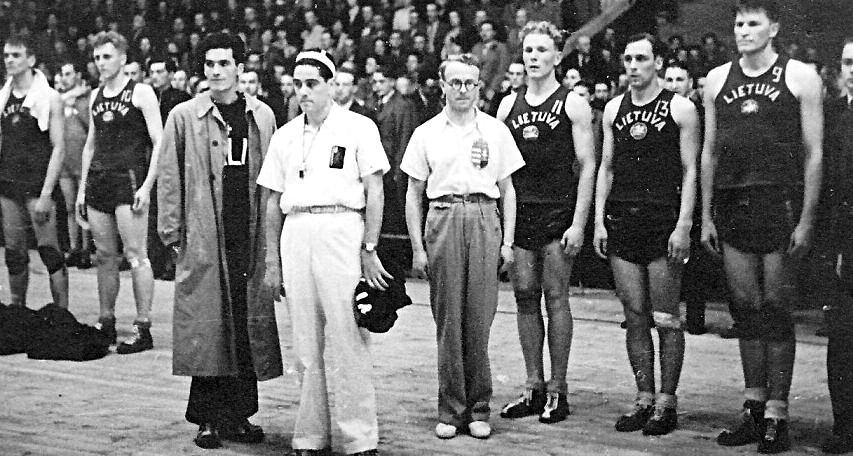

So how did your six-month stay in Lithuania go?

When we got there we were met at the station by a young athlete from the educational department. He took us to a hotel where they had everything all set up for us. We met the President of Lithuania. It was just wonderful. We went to banquet after banquet and for a week and a half we just had a beautiful time. But right before we had to return to the States, we took a side trip into the countryside to visit my father’s sister-in-law. It had been raining and the horse side-stepped a puddle and tipped the wagon over. My sister-in-law broke her leg. We had to return to a hospital in Kaunas, and we stayed another three and a half months. My dad returned to America because he had to work. Since this was basketball season, I was asked to train some of the Lithuanian athletes. I did for three or four months.

In the meantime, they also asked the Latvians, who were the previous year’s European champions, to play us. I said, “Oh no, we aren’t ready to play a championship type of game.” But we played them anyway. Fortunately for us, we beat the Latvian team. Then they did not want to let me go back to America. They said, “Oh, you must stay here.” I said, “No, I’m going to law school.” “You can study law here,” they said. Finally, they asked, “Would you consider coming back next year because we are having an all-Lithuanian Olympics in 1938 and the European championship in 1939?” Late in November we left Lithuania to go back to the United States, with my sister-in-law in a big cast on her broken leg. When we finally got home, I received letter after letter from the Lithuanian government asking me to return to Lithuania.

They were eager to have you come back.

My dad said, “You should go back. It’s my homeland and I’d like to see you help them.” Finally, in 1938 my wife and I went back to Lithuania and we coached various club organizations, teaching American style offense and defense. And they were quick to respond. They were free from Russian control only since 1918. So this is 18 years after their independence and they were anxious to learn everything: art, sports, music… I could have taught anything and they would have responded quickly because they were anxious to learn. And they did learn basketball— as I found out in years to come.

So this eventually led to the 1939 European basketball championship?

Right. As a coach I selected 14 players to represent Lithuania in the 1939 European tournament. They built a big pavilion that held 26,000 people. Maybe 12,000 were seated; the rest stood in aisles that were specially built. The tournament was actually settled in one of the first games. Lithuania played Latvia. It was a very fiercely played game. The Latvians played good basketball because they had sent three of their men to New York and to Philadelphia to learn the American-style basketball. They’d go to the YMCAs. They called it the “Yimca” (laughter). And they learned basketball there. Well, they were ahead of us, 36-35, in the last 10 or 20 seconds of the game. I was hollering from the center position to one of my teammates: “Please give me the ball. Throw it to me, I’ll score!” They finally got it to me and with one second left I scored a basket that beat the Latvians, the former champions, 36-35. I think they carried us around on the floor for ten minutes there. They couldn’t get the second game going, they were so excited. It was played in Lithuania, as I said, with a Lithuanian crowd. And they just carried our athletes around. I kept trying to tell them: “Please put the athletes down. We have to play five more games. Please put us down!” (laughter).

Latvia was the established European champ and also a main rival.

That’s right.

Were you the only American- born member of the team?

[ed. note: six players on the Lithuanian roster were born in the united states: Juozas Jurgėla (Chicago), Vytautas Budriūnas (Waukegan, iL) Phil Krause (Feliksas Kriaučiūnas – Chicago), Pranas talzūnas (Chicago), Mykolas ruzgys and Frank Lubin (Pranas Lubinas – Glendale, Ca)]Let me give you some very vital information. Lithuanians are regarded as Lithuanians all over the world. When you come back to Lithuania, they regard you as a Lithuanian and they give you a passport as a Lithuanian athlete. No matter where Lithuanians are they want to help Lithuania get established. Lithuanian-Americans were allowed to play for the Lithuanian team because they were allowed dual citizenship. They were considered Lithuanians in Lithuania. So I picked them up and we played with this team. We were fortunate to have them because the young Lithuanians were not too well-versed in basketball. But they became wellversed, as was indicated in the years after I left in 1939. The Russian team became very powerful in later years. And it was found out that they had taken up a lot of the young athletes that I had coached.

So you left a bit of a legacy behind in Lithuania?

That’s what they lay on my shoulders. So I don’t know whether I’m famous, or infamous, for having helped the Russian team by teaching the young Lithuanians how to play the American style of basketball. I don’t know. I just take it as it is.

Did Lithuanian officials encourage you to stay in Lithuania after 1939? Certainly the war will enter into the picture very soon.

Our consul called all the Lithuanian-Americans in and told us, “If you have any business arrangements here in Lithuania, you better start canceling them because things are not going to be good here in the next few months.” July and August was when it was really bad. He told us we better get out of Lithuania. He knew at that time that war was imminent. When the war started I was coaching a Lithuanian girls’ team and we were invited to play in Italy. When we tried to come back to Lithuania the war had already started. The Nazis had gone into Czechoslovakia. We couldn’t get across the border into Switzerland. So we contacted the sports organization that our girls had played against. Vittorio Mussolini, Benito’s son, was managing this club. He was the one that got the Swiss border guards to allow us to go through Switzerland to get into Germany. In Germany we had no problem at all. We finally arrived after our hazardous trip, and then my wife and I got on a boat to America.

Returning to the United States after the European tournament in 1939, I came back to Hollywood. My job at Universal Pictures was no longer there because they had fired all the players for having gone to the Olympic Games. Being a union member I was able to get a job at Twentieth Century Fox. Of course, being very interested in basketball, I and two others from our Olympic team joined their basketball team. The war hit us in 1941. I was drafted into the military. I went into the Air Force at March Field in 1942. They had thousands of soldiers there and they conducted regional basketball, football, and baseball games and track meets. I started running the basketball team at March Field. We had quite a number of big players.

You played up into your 50s, correct?

I was playing in my 50s against strong teams. I was in the YMCA ranks. They needed a center one time and I used to work out there and they said, “Come on and play with us.” So I played with the Hollywood YMCA for a number of games. But it was a different style of game. The young athletes, 18 or 19 years old, would come up and shake my hand and say: “I’m so-and-so, Mr. Lubin. My dad said to come up and say hello to you. My dad remembers when he played against you 25 years ago.” So that’s when I thought it was time to give it up. (laughter) I’ve been retired since 1967. From then I was through with basketball, except in preparation for the 1984 Olympics when I was called upon by the Olympic organization to join what they called the Spirit Team. We spoke at grammar schools, high schools and club organizations. We bring our gold medals sometimes. I do. When the older teachers of 40 and 50 say, “Oh, you’re an athlete.” I say, “Yeah, I’m human. I’m just like anybody else.” But they’ll say, “An Olympic athlete and a gold medal! I’ve never seen one. Can I hold it?” And they look at it and they ask, “How much is it worth?” And I say, “I don’t measure it in terms of money. It is a cherished thing for me.”

DRAUGAS NEWS Lithuanian World Wide News in English

DRAUGAS NEWS Lithuanian World Wide News in English