Lithuanian-American Management Theorist and Aviation Hero

by Henry L. Gaidis.

Vytautas Andrius Graičiūnas is one of the most noted Lithuanians, famous for his contribution to management theory. He studied how many subordinates a manager can best supervise and came up with an equation that is still widely cited today, showing that, as the number of people supervised increases in a linear fashion, the number of possible groups and relationships among those supervised rises exponentially, proving mathematically that the optimum number of subordinates should not exceed four or five.

Recounting his academic contributions in detail is beyond the scope of this article. Here, we focus on his interesting and multifaceted life story, which begins in Chicago, extends through Europe, including a stint as a World War I aviator, then moves on to Kaunas Lithuania, to end with his death under mysterious circumstances in a labor camp in Siberia.

Vytautas was born on August 17, 1898, in Chicago, Illinois, to Andrius Lucian Graičiūnas and Uršulė Varankaitė, immigrants born and raised in Lithuania. Unlike the vast majority of their fellow Lithuanian American immigrants, Andrius and Uršulė were not peasant farmersseeking the economic opportunities America offered, but were attracted by its liberty and freedom. Andrius came from a wealthy Kaunas family and grew up among the nation’s intelligentsia. He was a physician and a respected member of the Czarist aristocracy that ruled the country, yet he embraced the dream then sweeping the Baltic nation of a free Lithuanian state. Because of his political activities, Andrius soon had to flee his homeland to avoid arrest. He immigrated to America with Uršulė in July 1893 and settled in Chicago, where three sons, Vytautas, Algirdas, and Victor, were born. While living in Chicago, Andrius became a well-known surgeon. He continued to be a Lithuanian activist, working tirelessly for the good of less fortunate members of the Lithuanian-American community. Uršulė passed away while their children were still quite young, so it was left to the widowed doctor to instill in them a love of America and the dream of a free and independent Lithuania. His compassion to help others included welcoming his Lithuanian-born niece, Unė Babickaitė, into his home as a young adult.

Vytautas grew up in the Lithuanian-American community of Chicago, where he was a gifted pupil, and went on to graduate from the University of Chicago; not a small feat during an era when few Americans finished high school. Most of Vytautas’s biographies, after documenting his date and place of birth, and studies at the University of Chicago from 1914 to 1917, quickly move on to discuss his subsequent contributions to engineering and management theory. At most, there might be a single line of text indicating Vytautas had served in the U.S. Army in France from 1917 to 1919. These historians overlook that Lieutenant Graičiūnas was a World War I combat aviator. Lithuanians take pride in the postwar aviation exploits of Steponas Darius and Stasys Girėnas, but have forgotten Graičiūnas was the only LithuanianAmerican known to fly combat missions in the skies over France during the Great War.

“And now for the rest of the story,” in the words of the late radio commentator Paul Harvey, Jr. Vytautas Graičiūnas, a gifted university student, chose to leave his studies in April 1917, when he heard his nation’s call for volunteers to fight for freedom in World War I. Although the fighting, which had begun in Europe in 1914, became known for numerous technical innovations, none caught the imagination of the general public more than aviation. Prior to the war, military aviation consisted largely of flying over enemy troops and fortifications for reconnaissance; but with the advent of the machine gun and better aircraft, the pilot became romanticized as a modern-day knight taking to the sky to give battle with the enemy. It is not known what drew Vytautas to aviation, but he quickly volunteered and was approved for pilot training.

Unfortunately for biographers, a fire at the U.S. National Personnel Records Center in Saint Louis, Missouri, in 1973 destroyed sixteen to eighteen million records, including most World War I and World War II aviation service files. As a result, Vytautas’s military service records were lost to history. Two surviving National Archives index cards, however, document that Vytautas A. Graiunas (last name misspelled), served as a Lieutenant with the 9th Aero Squadron of the U.S. Army Aviation Service during World War I. From these scant cards and the U.S. Army’s military-unit histories, we can present the history of distinguished service by Graičiūnas and his fellow flyers who served with the 9th Aero Squadron.

After his induction into the U.S. Army in Chicago, Graičiūnas was assigned to Company E of the Provisional Aviation School Squadron at Kelly Field in San Antonio, Texas. On May 30, 1917, while receiving basic pilot training at Kelly Field, the members of Company E were separated as a unit to receive specialized bombardier training. On June 14, Company E was officially designated the U.S. Army 9th Bombardment Squadron, and upon completion of the training, each flyer was commissioned a 2nd Lieutenant in the U.S. Army. On July 5, these new officers were sent to Selfridge Field in Mount Clemens, Michigan, where they underwent special training in radio communication, and aerial bombing and photography. Here, Lieutenant Graičiūnas earned the aviator ratings that qualified him to wear the coveted pilot wings on his uniform.

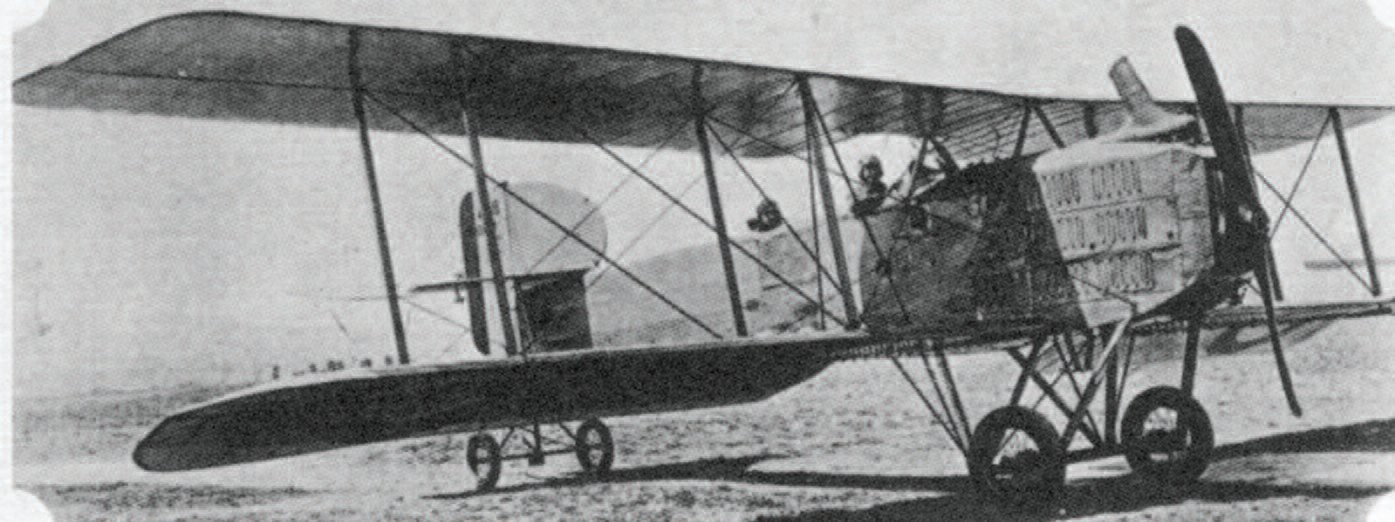

On October 27, 1917, the 9th Bombardment Squadron was ordered to Mineola Field on Long Island, New York, and on November 27, sailed from Halifax, Nova Scotia, to Liverpool, England. Arriving on December 7, the squad was assigned to the British Royal Flying Corps, Romsey Rest Camp, where they underwent another six months of combat training. They became the first American squadron to fight alongside a British unit. On August 7, 1918, Lieutenant Graičiūnas and the other aviators of the 9th Aero Squadron travelled to Southampton, where they boarded a ferry to cross the English Channel to Le Havre, France. They then used overland transportation to reach the Saint Maixent Aerodrome, the primary French reception center for American Expeditionary Forces. The unit was assigned to the Colombey-les Belles Aerodrome, where they were equipped with French Breguet 14A2 reconnaissance aircraft and became the first American squadron to fly night reconnaissance.

During the early years of World War I, both the Germans and Allies had learned to conduct troop movements at night to conceal their operations. The Breguet was equipped with a camera for recording and sometimes a radio for real-time reporting of enemy troop movements. The two-man Breguet crew comprised a pilot and an observer; the latter’s duties included tail gunner and bombardier, if necessary. The 9th Aero Squadron became part of the 1st Army Observation Group, Air Service, assigned to the Headquarters of the Night Reconnaissance Bombing Group at the Amanty Aerodrome in the Toul Sector, where it began to fly combat missions.

The 9th Aero Squadron began its first night patrols from the Vavincourt Aerodrome at Amanty on September 14, 1918, and flew regular missions over enemy territory. Lieutenant Graičiūnas was one of the brave young men who nightly risked their lives flying into combat for their country. Over the next three months of 1918, the 9th Aero Squadron took part in many famous World War I battles. They earned combat streamers for participation in the Battle of Lorraine–Tour Sector, August 30 to September 11; the Battle of Saint Mihiel–Offensive Campaign, September 12 to 16; and the Battle of Meuse-Argonne–Of fensive Campaign, September 26 to November 11.

Owing to the bravery and dedication of these flyers, a great deal was learned about night reconnaissance that is still useful. One of the units notable innovations was painting the underside of their aircraft black to conceal the planes from enemy searchlights and antiaircraft guns. During the war, it became customary for aviation units to adopt an insignia, which was frequently painted on aircraft and worn on uniforms as a distinctive patch. The insignia of the 9th Aero Squadron featured a double-winged aircraft flying solo through enemy searchlight beams that form the Roman numeral IX. Although most American units were sent home shortly after the November 11, 1918 armistice, the 9th Aero Squadron was assigned to the U.S. Third Army Air Service, VII Corps Observation Group, and sent to the German Coblenz Aerodrome at Fort Kaiser Alexander, where it was part of the Allies’ Rhineland occupation force. There, the unit served as a courier squadron to Third Army Headquarters and also flight-tested surrendered German aircraft. The unit was subsequently assigned to the VII Corps Observation Group at the Trier Aerodrome in Germany and the 1st Air Depot at Colombey-les-Belles Aerodrome in France. Upon finally receiving their orders to go home, the squadron was assigned to Marseilles, where they remained from May 25 to June 7, 1919, when they embarked on a ship to the United States. Upon arriving home, most personnel were demobilized at Mitchell Field, New York and, with the thanks of a grateful nation, returned to civilian pursuits.

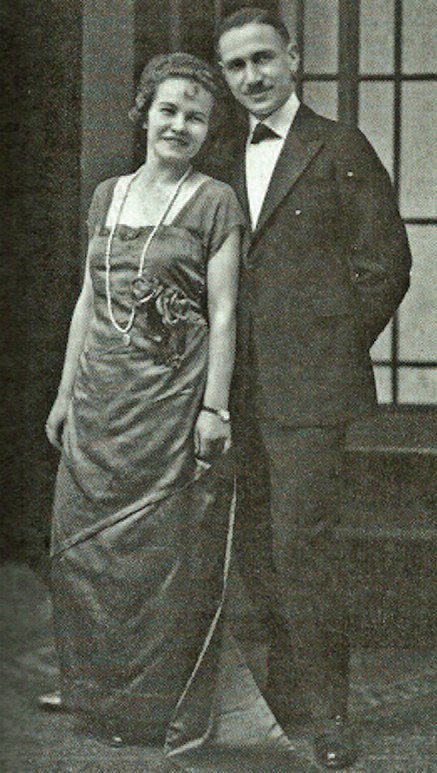

Once back home, Graičiūnas renewed his studies at the Illinois Institute of Technology, where he earned his Master’s degree in 1923. For the next three years, he worked as a management consultant in Chicago, Milwaukee, and New York. Although the young graduate was filled with a passion for his work, he also found time to fall in love with and marry his cousin Unė Babickaitė, who had grown up with him in his father’s house. In 1927, Vytautas abandoned a promising engineering and management career in America to move to Lithuania.

Graičiūnas quickly obtained employment in Lithuania and for the next several years managed a number of factories in Kaunas. As his skills became known and because the industrial capacity in Lithuania at the time was very limited, he began to travel as an international management consultant. Although Lithuania remained his home, he practiced in Germany, Switzerland, France, Holland, Spain, and England, and served the Lithuanian government as a consultant to the Ministry of Defense. He was also a frequent lecturer at Vytautas Magnus University. For his service to the Republic of Lithuania, Graičiūnas was awarded the Commander’s Cross of the Order of Grand Duke Gediminas. He founded an organization of management consultants in Lithuania and became its first president.

Although Vytautas and Unė surely saw the storm of war spreading across Europe during the early days of World War II, they chose to remain in Lithuania and survived the Soviet and Nazi occupations. During the initial 1940–41 Russian occupation, he worked for the Soviet government as a consultant to the People’s Commissariat and during the Nazi 1941–44 occupation served as a Management Advisor to the German Agriculture Business Directorate-General. As an American citizen, Vytautas could have returned to the U.S. at the end of World War II, but Vytautas and Unė decided to remain in Soviet-occupied Lithuania, to support their homeland. During the second Russian occupation, he taught as an Associate Professor of Civil Engineering at Vytautas Magnus University from 1945 to 1948, and then worked as a management consultant for the “Kotton” and “Silva” stocking factories in Kaunas from 1948 to 1951.

Although Graičiūnas was not immediately targeted by the Russian authorities, the situation changed as the Cold War intensified. On the night of April 18, 1951, Soviet secret police raided the Graičiūnas apartment in Kaunas, and Vytautas and Unė were arrested for alleged espionage and anti-Soviet activities. They were summarily tried and imprisoned in the Siberian Gulag. On January 9, 1952, Vytautas died under mysterious circumstances in the Olzheras (now Mezhdurechensk) camp in Kemerovo Oblast, Siberia. After Stalin’s death in 1953, Unė was allowed to return to Kaunas, where she lived out the rest of her life.

To this day, in management textbooks worldwide, Graičiūnas’s equation and other principles of management organization developed by him are widely cited, discussed, and analyzed. In Kaunas and Vilnius, the names of the campuses of the Vytautas Graičiūnas School of Management (www.avm.lt) pay tribute to his intellectual accomplishments.

DRAUGAS NEWS Lithuanian World Wide News in English

DRAUGAS NEWS Lithuanian World Wide News in English