By Vereta Rupeikaitė.

A pirtis is a creation of both man and nature. In almost all lands where the weather gets cold, the need arose to experience complete, cleansing, body warmth and, at the same time, shake off nagging worries and negative thoughts. Heated stones splashed with water are used to generate moist heat and steam, which adheres to and penetrates naked skin lightly stimulated by whisking with warmed fronds of birch and aromatic flowers. The hot steam envelopes and soothes those in the pirtis with herbal essences emanating from the plants in the whisk. Regular visits to a pirtis, often at least once a week, were and remain an important part of country living in Lithuania.

If you’ve ever had the chance to visit a pirtis, to whisk your skin to a warm glow, then to cool off with pure water from a nearby river, lake or well; you know there is never a need for soap! Or perhaps you’ve had the oportunity to wash your skin with heated water to which various forest grasses have been added. Today’s cosmetic industry strains to develop creams and lotions that beautify and rejuvenate, but nature’s bounty has always been there to accomplish the same goal.

Like the Finns, Lithuanians can be proud of their longstanding traditions of going to a pirtis; customs that undeservedly became forgotten by some. Fortunately, in Lithuania today, a new generation of health seekers is rediscovering the benefits of the pirtis and the old customs related to it, and is developing new traditions around this restorative experience.

At Kernave, in the Pajautos Valley, archaeologists have found remnants of structures serving as pirtis buildings dating back to the fourteenth century, along with their stoves and remnants of birch whisks. One can surmise, however, that Lithuanians made use of pirtis huts much earlier.

Historical sources describe how Lithuanian nobles included pirtis overseers as part of their entourage, accompanying them on their travels. Small, simple pirtis cabins were erected in country orchards and gardens, and, in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, wealthy boyars made large pirtis buildings available to all the inhabitants of their manors.

Estate pirtis structures could be elaborate and sometimes even comprised an entry hall. At Rumšiškes, in the Kaišiadorys region, there is a museum dedicated to country life in Lithuania during various historical periods. Here, they have restored a seventeenth-century pirtis constructed by a wealthy landowner. Five years ago, this “Dvaro pirtis” (Dvaro = estate)was made fully functional. Once a week, Lithuanian enthusiasts from all over the country visit the Dvaro pirtis; and if they have friends visiting from other countries, they are sure to bring them along for the unique experience.

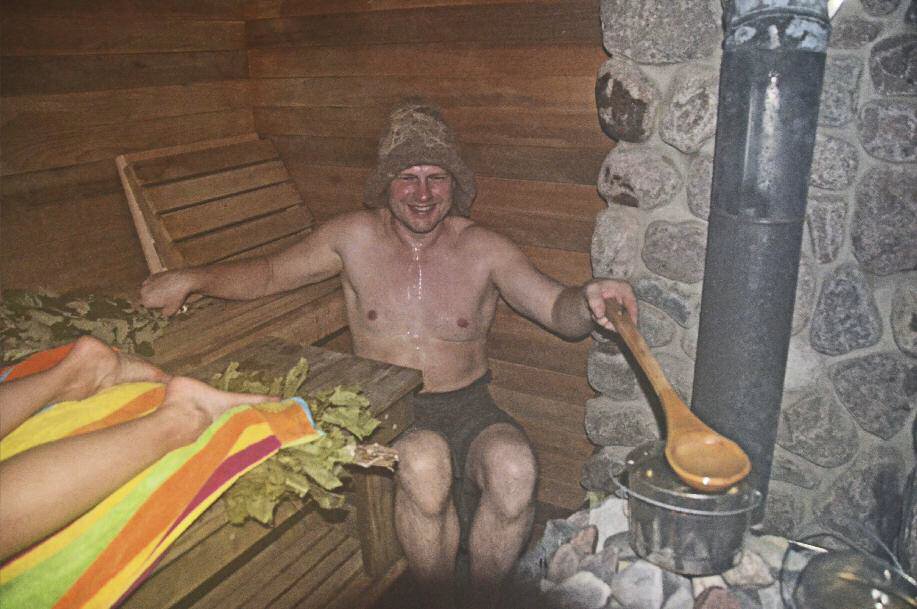

On many days of the week, the Dvaro pirtis is open to all comers. Many who visit see, for the first time, the process and ritual of forming “enhanced” water, when heated rocks are placed into a wooden bowl filled with water. For many years, even before containers made of clay or metal came into use, water was heated in this manner. Such water was believed to have healing properties and was used to bathe newborns. To describe or to film this process of enhancing water is not possible; one has to experience it.

This Dvaro pirtis functions year round and is one of the largest steam structures in Lithuania. It can comfortably accommodate twenty people, but often up to thirty happy pirtis lovers will be found inside, enjoying the gentle microclimate created by an enormous brick stove holding two tons of heated stones. These stones are heated, sometimes red-hot, by a flame that is visible upon opening the door of the stove. Persons in the pirtis regularly open this door to pour water on the heated stones, after which jets of steam surge out, maintaining the desired level of heat—never more than 60 degrees C (140 degrees F).

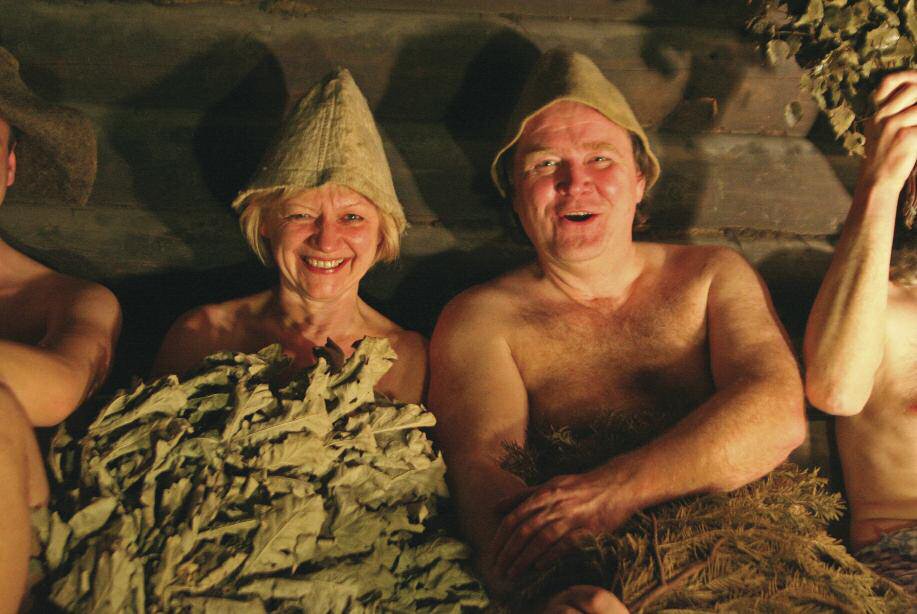

The high point of a visit to the pirtis is the thrashing, or really, more gently, whisking. This is a ritual involving steam, leaves, and water, after which the participant feels as if born again.

The Lithuanian pirtis is stirring interest in people from other countries. In early summer of 2014, the XVI Sauna Congress was held in Trakai, Lithuania, attended by health enthusiasts from all over the world. An especially large delegation came from Japan. The US was represented by sportsman and physician Dr. Mark Timmerman.

Of German descent, Dr. Timmerman grew up in the northern US, in a state where there is a large number of immigrants from Finland who have continued the tradition of the Finnish sauna in America. Dr. Timmerman, like his neighbors of Finnish background, had often visited Finnish-style saunas in the US, but had never seen nor used whisks.

During his visit to the Sauna Congress in Lithuania, Dr. Timmerman visited the Dvaro pirtis and, for the first time, had the experience of being whisked by bundles of leafy branchlets of oak, birch, and juniper. Transported by the enveloping steam, the aromas of natural woods and leaves, and by the sounds and other unique aspects of the Lithuanian pirtis, Dr. Timmerman stated that he was experiencing a new dimension of hot-steam bathing. Up to that time, he had simply sat in his sauna at home waiting for his body to warm up, after which he would refresh himself in the cool waters of his swimming pool.

On returning to Wisconsin, the good doctor invited the Dvaro pirtis aficionados to visit, and he enlisted them to show other guests how these leafy fronds with their aromatic properties, could magnify and enrich the hot-steam experience; and how, by whisking, one could achive a soothing massage and energize the body with the herbal powers of nature. Dr. Timmerman decided to adopt this new whisking experience for himself.

During their visit to Wisconsin, Vereta Rupeikaite and Valdas Rimavicius, frequent regulars at the Dvaro pirtis in Lithuania, shared the knowledge of the Lithuanian experience with their American hosts. Dr. Timmerman was soon binding his own whisk bundles from maple, oak, and birch branches and leaves from his own backyard.

Dr. Timmerman decided to modify his Finnish-style sauna, to make it more like a Lithuanian pirtis. The stairs were removed and a platform was created, on which one could comfortably recline and be whisked. The commercial oven was modified, doubling the volume of stones within. The host was astonished that, with these modifications, the thermometer in the pirtis showed a lower temperature than before, even though the feeling of heat was markedly intensified. The steam was not burning hot, but mellow and gentle; the whisk leaves did not dry out, but remained moist and supple, filling the air with nature’s aromas.

Dr. Timmerman decided to construct a separate steam hut that would closely resemble a Lithuanian pirtis, equipped with its traditional brick stove, and, of course, to always whisk. Once having been whisked, Dr. Timmerman no longer wished to go to a steambath without this part of the experience.

Most steam huts and saunas these days are equipped with chimneys. For this reason, their walls and ceilings are never sooty, unlike the pirtis buildings of old. In those, when the stove was initially fired up, the pirtis would fill with smoke. Once the rocks in the stove had become hot, the smoke would be cleared out, and the pirtis was then ready for use. In the Open Air Museum of Lithuania, eight authentic country-style smoky pirtis huts have been reconstructed, but they are small and not in use. One can view in them stoves made from gathered stones and benches on which peasant farmers once sat, bathed and whisked each other, and shared their daily cares and joys.

In many Lithuanian hamlets, especially in the regions of Aukštaitija and Dzukija, one can still encounter old-fashioned pirtis huts. In many of them, the users still adhere to the old traditions, bathing together with their neighbors, and creating enhanced water.

Today’s enthusiasts in Lithuania are, bit by bit, gathering traditions about the pirtis that were never written down and, in many cases, have disappeared. One example is the work of ethnographer Stasys Daunys, who recorded his own findings about the pirtis culture in Lithuania, and also collected the findings of other researchers. At one time, Daunys worked at the Open Air Museum of Lithuania in Rumšiškes, and it was largely due to his initiative that the present Dvaro pirtis was recreated. In his view, the preparation of the pirtis for use—the stoking of the fire, the whisking, the bathing, and the shared experience, were all a form of community ritual that played not only a physical, but also a spiritual role.

Obviously, in today’s world, where most houses have modern plumbing, bathing is no longer the primary object of going to a pirtis. Today, people go there to seek better health, perhaps to strengthen their ability to fight off disease, to slow down the tempo of their lives, and to reduce levels of stress and fatigue, as well as to renew their relationship with nature and spend time with friends and family.

During Soviet times, unfortunately, the pirtis became a place where one would go to have a good time in the evening, mostly linked to the use of alcohol. In those pirtis huts, electric stoves would be used, because they required little work to start up and tend. Today, they are called Finnish-style saunas, because Finland is where such electric stoves were first widely used. In such saunas, however, the microclimate is quite dry and the temperature can feel burning hot.

Not widely known is the fact that, historically, the traditional Finnish sauna was not characterized by dry, burning heat. The Finns also had smoky steam huts with stoves full of stones, in which they whisked each other with leafy branches. For some reason, the tradition of whisking in Finland more or less died out. The president of the International Sauna Association, Riso Elomaa, who is Finnish, recently praised the continued Lithuanian tradition of whisking while bathing in steam.

Whisking enthusiasts from different countries organize international conferences, seminars, and even contests. One can see that the concept of whisking, as a type of massage, will soon play a greater role in the traditions of many countries; often, all that is required is remembering and revitalizing their own local practices.

It is a bit sad, that many Lithuanians don’t realize they have their very own traditional pirtis and mislabel it a “Russian” steam hut. But the culture and unique traditions of the Lithuanian pirtis are becoming more widely known throughout the world, and Lithuanians should be proud of their heritage in this area.

DRAUGAS NEWS Lithuanian World Wide News in English

DRAUGAS NEWS Lithuanian World Wide News in English